In the preface to the 1970 edition of his classic text Mythologies, the French literary critic Roland Barthes invented a new term, namely semioclasm. Like its more well-known counterpart iconoclasm – the act of criticising cherished beliefs or institutions – semioclasm also constituted a form of canon-questioning. A semioclast was someone who turned their critical gaze upon the various “sign-systems” that Barthes called “collective representations,” which had acquired the status of myth.

By myth, Barthes was not referring to acts of fabricating or believing in lies. He never presented mythology as the pure opposite of fact. Rather, Barthes argued: “Semiology has taught us that myth has the task of giving an historical intention a natural justification, and making contingency appear eternal” To put it in the simplest terms, for Barthes, myth making emerged from the desire for eternal principles or categories that somehow provided a form of psychological relief from divergent and contingent facts, experiences, and uncertainties of a single life. We might think, for example, of a binary struggle between Good and Evil, or forms of absolutist faith in institutions such as The Church, The Family, The Party, The Race or The Nation.

The point is not that such categories or institutions are inherently wrong-headed. The point rather, is remaining aware of and sensitive to how such categories can seemingly create stone-like, unbending ways of thinking and so too, codes of conduct. We might think of how traditional views of the family often justify specific gender roles, how racial doctrine naturalise discrimination, how fundamentalist religious doctrine offers a rigid matrix for judging behaviour, or how party politics might demand absolute loyalty over the continual use of one’s own discernment. With this in view, Barthes turned the tools of semiology – the study of signs and symbols and their usage and interpretation – onto the human tendency to attach transcendental meaning to almost anything. Every fact could always be read as bound to and so reflective of a web-like system of multi-sided meanings. Wrestling matches, plastic dishes and advertisements for detergents are just some of the socio-cultural phenomenon on which Barthes performed his semioclastic readings.

There is something to be gleaned by reading Mythologies in our own moment, marked as it is with the tides of misinformation. Read carefully, Barthes’ text is scattered with well-positioned lookouts, which offer different perspectives on current conflicts over how best to discover and then safeguard the truth. As a way of connecting the threads, a recent study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management on the spread of misinformation during election periods in the United States found that known falsehoods are 70% more likely to be re-tweeted on Twitter than verified facts. Thus, the problem of misinformation seems not to be a matter of simply having access to rigorously vetted facts, but rather that somehow falsehoods can be so alluring, so tempting and so satisfying to begin with. Somehow, the garb in which information (or misinformation) arrives matters for how it is received.

As I have argued elsewhere, our current era of misinformation is but the most recent episode in a much longer liaison between the arts of ‘spinning’ the truth and the pursuit of any number of political or personal ends. What history teaches us is the extent to which not only is “misinformation” old, but it has never come down to a simple sorting of the differences between “truth” and "lies.” For after all, such studies argue, the truth itself is often hard to disentangle from webs of bias and subjectivity, let alone from quests for power or profit.

Beyond the bounds of history, a growing body of psychologically-anchored work on “motivated reasoning” – or people’s tendency to reason according to their pre-existing biases – has cast further doubt on the ability of “fact-checking” to counter the prevalence or acceptance of falsehoods. Through this work, we can see that there may not be any stable correlation between the circulation of rigorously-checked facts and the willingness to believe those facts. What that literature does not address, however, are the more philosophical dimensions of why and under what kinds of conditions people do or do not believe certain propositions or storylines.

I want to suggest that a broadened perspective on the dynamics of misinformation include an effort to even further de-couple the question of ‘facts’ from questions of belief and the need for existential certainty.

There is an extent to which one’s perceived sense of security, personal identity or sense of personal power and self-importance can become tied to any number of ‘grand narratives,’ from myths of racial superiority to myths of an earth of unlimited natural resources. In her Crisis of the Republic, the philosopher Hannah Arendt cast some additional light about the appeal of false narratives. She argued that many lies “work” because they appeal to our “wishes” and “expectations.” By contrast, Arendt claimed, “Reality has the disconcerting habit of confronting us with the unexpected, for which we were not prepared.” This is very close to Barthes’ view that the power of myth rests in its ability offer up eternal categories that help us feel confident, secure and even in some way immortal. Thus this craving for peace of mind can override any quest for ‘facts,’ –mentally destabilising as they can be.

The question, then, is what do these insights mean for historians and their craft?

Once again, Barthes left some clues.

What could be more straightforward, or seemingly less ripe for serious analysis than a wrestling match? Feats of strength and stamina, a dance-like struggle for domination, performed not for survival in the barest sense (though money is at stake), but rather for entertainment. Yet for Barthes, the sport of amateur wrestling (or in French, le catch) became the opening case-study in his effort to discern the work of myth in modern, secular societies. Of wrestling Barthes pinned in Mythologies: “Even hidden in the most squalid Parisian halls, wrestling partakes of the nature of the great solar spectacles, Greek drama and bullfights: in both, a light without shadow generates an emotion without reserve.” Under the glare of neon lights, with nowhere to hide, two figures (man and man or man and beast) offer the audience a cathartic resolution typical of theatrical tragedy – the end to suffering and violence, born of suffering and violence.

By folding time in on itself – ancient spectators spill into seedy twentieth century Parisian wrestling halls – Barthes spoke to the primeval heart still beating in the modern chest. Barthes argued that for the audience, it did not matter if the match was rigged and therefore fake. What mattered was that for a moment in time, the struggle between two clichéd characters, offered up a simplified world, a clear contest between good and evil, that could be won, settled, resolved, put to rest. Life, by contrast, rarely offers terms so neat, so binary or so final. It is not the authenticity of the event, then, but the emotional and psychological needs that it meets, that sells tickets.

Myth is a way of making ‘facts’ correspond in some absolute way with a normative system of meaning. This explains why mythology makes such ready use of the cliché.

In Barthes’ reading of a mundane spectacle such as a wrestling match, we find surprising tools not only for continually reading the world around us, but also for thinking about and writing history, in an age of misinformation. Barthes argued: “We reach here the very principle of myth; it transforms history into nature.” The history of the wrestling match would include the nuances of how the sport came into being, its funders, its advertisers, the social milieu and biographies of the wrestlers, the distribution of profits, the demographics of the typical spectator and so on. The mythological function of the match, by contrast, happens at the moment when all those contingent, complex ‘facts’ disappear and are replaced with the eternal concept of Good and Evil. In that rendering, every single match, night after night, re-performs the eternal struggle, and so is in some way always reducible to it. For the spectators, this ritualised performance of absolute principles provided relief from the cognitive dissonance of reality, replete with discordant details (heterogeneous choices, diverse constraints, and non-linear consequences).

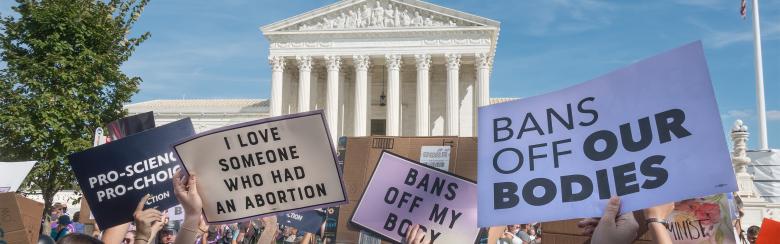

Here then we see the inner workings of myth. Again, Barthes argued: “This confusion can be expressed otherwise; any semiological system is a system of values; now the myth-consumer takes the signification for a system of facts; myth is read as a factual system, whereas it is but a semiological system.” That is to say, myth is a way of making ‘facts’ correspond in some absolute way with a normative system of meaning. This too explains why mythology makes such ready use of the cliché. As Barthes argued: “But in general myth prefers to work with poor, incomplete images, where the meaning is already relieved of this fat, and ready for a signification, such as caricatures, pastiches, symbols, etc.” In the wrestling match, the man behind the costume, his full life, is rendered meaningless, only the role remains. While this might not be so surprising in a spectacle designed for entertainment, we can think of countless real world examples, of how “mothers,” “fathers” or “functionaries,” somehow cease to exist beyond the roles they come to play. Or perhaps even more poignantly, in his essay “The Problem of Blackness”, Franz Fanon explained what it meant to feel one’s life absorbed, from the inside, into the innumerable stories told about race. On the one hand, Fanon knew himself, the sensations of himself as the man who reached for and then smoked a cigarette, a visceral, experienced “self.” But on the street, a little girl cried: “Mama! See the Negro! I am Frightened.” And in that moment, beheld by terrified, young eyes, Fanon explained: “I could no longer laugh because I already knew that there were legends, stories, history and above all historicity…Then at various points, the corporeal schema crumbled, its place taken by a racial epidermal schema.” Like the wrestler, in the eyes of the others, a black man could only ever be spectacle circumscribed by legend repeated, and never a full or fulsome life.

On this point, Barthes also provided more patently historical examples: “A French general pins a decoration on a one-armed Senegalese, a nun hands a cup of tea to a bed-ridden Arab, a white school master teaches attentive piccaninnies; the press undertakes every day to demonstrate that the store of mythical signifiers in inexhaustible.” In each of these cases, the French Empire expresses itself in the symbolic garb of “Humanity” or “Civilisation,” and so reduces each subject to the symbolic dramaturgy of receiving the fruits of progress. A number of historians have also cast light on the processes by which power dresses itself in the mythos of eternal categories. In the book The Invention of Tradition, historians Eric Hobsbawm and Terrance Ranger demonstrated how modern nation states often give an aura of ancientness to political rituals and traditions that were in fact very recent. According to their thesis, the mythology of tradition generated an aura of legitimacy for governments seeking the loyalty of citizens and subjects. In their view, the historian’s role was to de-mythologise in order to reveal the workings of state power and governmentality.

In some ways Barthes too was interested in invented traditions. However, it is important to note that Barthes did not set out to de-bunk myths as much as he advocated learning to decode their unique dialect. In these terms, especially bigoted national or imperial “mythologies” are quite easy for some of us – already critical of racism and empire – to spot and decode. And yet, if we follow Barthes’s logic to its end, somehow we also have to accept that myth is everywhere, constantly aiding us in making sense of the world. The myths that will be most difficult for us to identify and question are the ones that we share, the ones we use to navigate our world. The best we can hope for is to sharpen our ability to observe, deconstruct and read myth as a way of disrupting its seamless claims to the TRUTH.

Rethinking the role of the historian as a semioclast might also push back against the social and political misuses of history, whose naturalisations support not only eternal categories but also feed the tides of misinformation. In both cases, Barthes’ view of myth reminds us that even the most solid facts might not be able to guard against the mind’s quest for soothing stories replete with the aura of eternity.

Some critics of “post modernism” might be afraid that Barthes’ view only takes us deeper into the terrain of “post-truth.” And yet, to be a semioclast is not to deny that truth might exist, it is only to be aware that it rarely arrives naked, undecorated in a value-system. As Ethan Kleinberg has argued: “The critics of postmodern theory are awash in nostalgia for a moment that never was. They appeal to figures who spoke frequently of the “common good,” like the US founding fathers such as George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, but without deep reflection on who was considered to be part of the common good and who was to be excluded.”

Semioclastic history would do precisely that work of reflecting. It would read the multiple “sign-systems” competing for a monopoly on the definition of the “common good.” Such a history would then take as its task revealing the myriad of ways in which differing definitions of the “good” each sought to naturalise a different sorting of who would be “inside” the commons and who would be left “outside.”

In sum, a semioclast’s work is never over.