The pandemic caused by the spread of covid-19 and the economic consequences of the measures taken to mitigate it are putting Latin American political systems in tension. Our series of webinars explore the effects of the crisis on democracy and state-citizen relationships across countries.

The case of Peru was on focus on July 30, 2020, with the participation of Prof. Paula Muñoz Chirinos (Del Pacifico University and Red de Politólogas), Prof. Adriana Urrutia (University Antonio Ruiz de Montoya) and Prof. Martín Tanaka (Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú).

The events are coordinated by Daniela Campello (Getulio Vargas Foundation) and Yanina Welp (Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy).

The situation in short

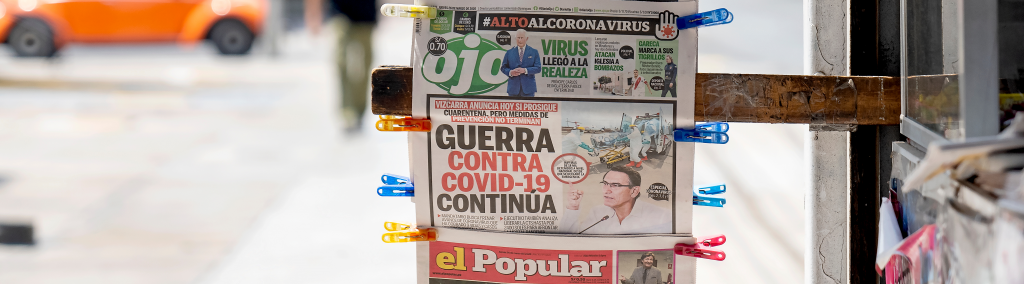

If the social outbreak in Chile in 2019 blew up the idea (anyway questioned by many scholars) that the country was an emblematic model of liberal democracy, now the pandemic has blown up ‘the Peruvian economic miracle’. The country that has grown the most in the Latin American region in recent decades faces the pandemic with a precarious health system and without state capacities to provide economic aid to the affected population. This means that although the president surrounds himself with experts and takes care of informing the population, the effectiveness of the measures is low. The contagion data is skyrocketing and the hospitals are collapsed. With low state capacities and deep political weakness, the situation has become critical.

Main points emerging from the conversation

1. Political will is not enough

President Martín Vizcarra (2018-) surrounded himself with experts, took care personally of communicating the population the evolution of the pandemic, took measures quickly, approved financial aid, purchases of tablets to promote online education, etc. His popularity had grown despite having come to the government after the resignation of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (Peruanos por el Kambio, PPK, who was facing a second impeachment trial with no prospects of avoiding removal, after having managed to circumvent the first). Vizcarra has popular support but does not have a political party and reelection is not allowed. Thus, uncertainty dominates the political scene.

2. Low state capacities.

The lockdown, suspension of public events, and closure of a good part of the economic activity were measures taken in March when the effects of the pandemic were being felt in Spain and Italy. Frontiers and airports were also closed and a curfew was established. However, hospitals were in a precarious situation and by July they were on the verge of collapse with a sustained growth of hospitalizations and infections. The government approved economic aid for the most vulnerable population, but the lack of records and the inefficiency of the procedures meant that many people who could benefit did not have access to them. The same applies in areas such as education. The purchase of tablets for the students was approved. The resources were available but it was not possible to activate an adequate purchase procedure and after two months these devices are still not available.

3. The economic growth of the previous decades did not promote welfare

The economy that grew the most in the region over the last decades reached the pandemic with 150 beds in emergency units for 30 million inhabitants. This eloquently shows that economic growth per se neither guarantees nor leads to greater well-being. But also, the speed and depth with which the economy has been affected make evident the weakness of this economic growth.

4. The limits and negative consequences of having a democracy without parties

Not having political parties leads to countless coordination and communication problems. The weakness of the public sphere, of the parties, and of civil society leads to a consistent decline in support for democracy. Political reform is still pending. Representatives in congress follow their own interests more than programmatic lines, and at the subnational level local parties proliferate for each election and disappeared shortly after.

5. The danger of the re emergence of an authoritarian populist leader

The economy was quickly affected, which, added to everything previously described, make our analysts fear the reemergence of an authoritarian populist discourse, something like a new Fujimorism backed by the demand for ‘mano dura’ (heavy-handed approach).

Link to the full event in Spanish: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ow1weJABxZo