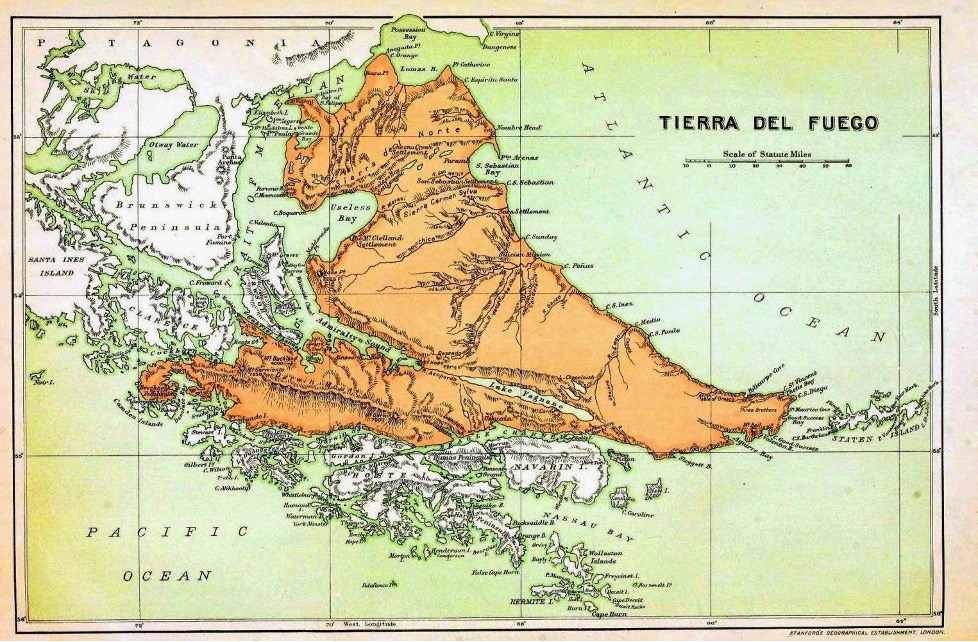

In 1908, the 100th anniversary of the Chilean Nation-State, a nationalist intellectual, Marcial Vicuña, embarks on a journey to support President Pedro Montt's new nation-building project aiming to embrace Chilean settlers and Indigenous people to foster peace. As part of his expedition, Mr. Vicuña reaches the island of Chiloe in the central region of Chile, to meet a couple named Rosa and Segundo Molina. Rosa, an Ona indigenous woman, had endured the horrors of rape and genocide inflicted upon her people in Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost part of the South American continent, by the ruthless employees of the Spanish landowner, José Menendez. Segundo, a mestizo (half settler half indigenous), on the other hand, had initially assisted Menéndez's employees in their violent acts. But eventually, unable to bear the guilt of his complicity, Segundo had escaped with Rosa. Upon arriving at their residence, Mr. Vicuña presents himself: “Marcial Vicuña, I work for the president”. ”What president?” answers Rosa defiantly. Vicuña then pressures Rosa into receiving him and his assistant in her home. Fearing the potential arrest of Segundo, due to his past association with Menéndez, Rosa agrees. Vicuña then meets with Segundo promising to absolve him if he collaborates in the new nation-building project: he wishes to film Segundo denouncing the crimes he witnessed. “Why do you care so much talking about this,” asks Rosa. “To bring justice” answers Vicuña. “Justice?” says Rosa with suspicion. Despite her skepticism, Segundo agrees to collaborate. As Vicuña positions the couple in an ‘authentic’ Chilean staging, they begin filming. However, with her gaze fixed on the camera, Rosa refuses to fulfill her role, disregarding the director's guidance. Vicuña out of his depth shouts at her: “ Rosa do you, or do you not, want to be part of this Nation?”

This striking scene from the movie Los Colonos (The Settlers, 2024) sheds light on how the development of the Chilean Nation-State in the 20th century was based on concealing mass rapes, traffic, and murders of southern indigenous people, followed by their coercion into “reconciliation” and assimilation into the Nation-State. The scene also hints at the intricate dynamics of indigenous and mestizo individuals, exploring their roles as both victims and collaborators: coerced, partially coerced, or even willingly participating in perpetuating violence against their own communities. Additionally, this scene portrays the contrasting roles played by women in the events surrounding Chilean nation-building, particularly through the opposing characters of Vicuña's assistant, a white woman involved in this coercive nationalist project, and Rosa, who defiantly resists any attempts to infringe upon her autonomy in the face of colonial gendered and sexual violence.

Nourished by the tales of my great-grandfather Manuel Rojas, a prominent Chilean author who claimed to originate from the Picunche indigenous people of central Chile, I was curious about this family heritage; in school, however, barely any attention was given to the history and fate of the indigenous peoples. Turning to alternative sources such as books and films helped me realize that Chile was a nation built on genocide that tended to deal with its historical violence by avoiding the subject altogether. The previously described scene appears in Chilean director Felipe Gálvez’s latest movie Los Colonos, in which he attempted to lift this taboo. Described by El Pais as “a stark and violent 'Western' that confronts Chile with its sins of colonialism”[2], this movie raises awareness of the prevalence of white supremacist and patriarchal violence directed at the indigenous populations of Tierra del Fuego in the context of its colonization, which began in the 1830s, the post-independence period[3].