After the movie Everything Everywhere All at Once received Oscar recognition in 2023, the phrase “Daughter that lives a Westernized life (生活西化的女儿)” (created by China News[1], a state news agency under the Chinese Communist Party) went viral on Chinese social media. The phrase first referred to the lesbian character played by Stephanie Hsu; later, the portrayal of the character's Chinese nationality and her homosexual identity emerged from the movie screen, revealing the complexities and interrelation of these two identities. The indirect approach to addressing queerness and Western influences signifies a national commitment in promoting a heterosexual lifestyle. This is achieved by marginalizing, excluding, and erasing individuals whose sexual orientations do not align with the communist ideology. By doing so, the Communist Party can reinforce the preferred societal norms and values. The portrayal of a lesbian character challenges the reserved and conservative patriarchal states and Chinese families' denial of the fact that they are not heterosexual or, with a nationalist narrative, the daughters of a family and a country. The phrase highlights Chinese nationalism’s denial of homosexuality and its efforts to conceal lesbian identities.

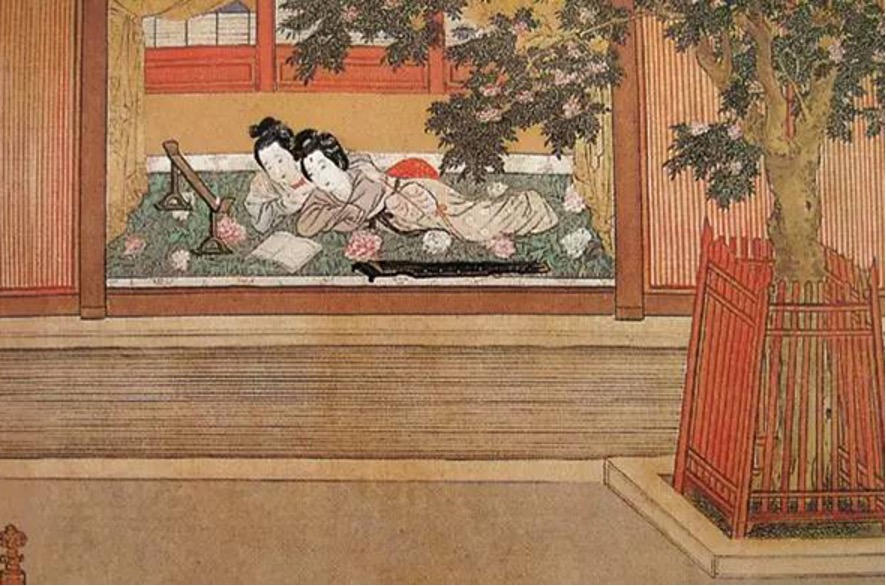

However, the existence of homosexuality in China can be found in Chinese literature dating back to the Shang Dynasty (16-11 Century BC)[2], such as in Zuo Zhuan, where the term “Luan Feng (鸾凤)” would be used to indicate a romantic friendship between two male friends in gay literature. The presence of lesbianism in Chinese history is concluded as having “a long but usually hidden history, and comes to light only occasionally.”[3] Nonetheless, lesbians also found various ways to gather and identify others without directly referencing their sexuality. For example, at the end of the 19th century in Shanghai, there was a group that used lesbian sexual behavior known as “Mojingzi,” which directly translates to rubbing mirrors in Chinese, and named themselves “Mojing Dang.”[4] These suggest that before communist China, lesbians often gathered and existed among themselves in hidden or reserved ways.

Under traditional Confucian values, which emphasize family and societal harmony, homosexuality and acts are viewed as immoral and harmful as the desire to keep the family intact is ingrained into society, as Adamczyk writes [5]. Moreover, as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rose in power in a country that Confucian values have long guided, non-reproductive relationships continue to be suppressed in China as it does not benefit the state. Thus, since the post-Maoist period, phobia towards same-sex behaviors and marriage has remained intolerable and invisible. For example, homosexuality is punished because it is “believed to damage population growth and economic development,”[6] and China needs patriotic values for national success. The crackdown on homosexuality by the Chinese State was harsh during the Cultural Revolution, and homosexual acts were seen as a violation of the moral principles of Chinese Society [7]. Homosexuality is punished because it is believed to harm population growth and economic development. The government stresses the need for patriotic values to achieve national success. As Jing states, “It was only after 1949 that homosexual behavior was seriously punished in China and served as grounds for persecution during Chinese political upheavals between the 1950s and 1970s.”[8] There was an equivalent being drawn between homosexuality and the West, as the Confucian society denied it.

The Chinese communist state often views Western influences negatively, considering them a threat to national integrity and traditional values. It can be seen through the anti-western sentiment in China and anything with a Western cultural influence as a threat, insult, or biased view to China’s stability and livelihood. Xu’s argument outlines the fear and feelings of the communist state, “the Chinese leaders understand that to incite patriotism without any opponents is impossible and that Chinese nationalism would not be sustained without an obvious rival [9].” Thus, in Beijing’s logic, as long as no signs of Westernization are shown, the nationalist image can be maintained. As a result, labeling something as "Western" is frequently used as an insult, implying that it is detrimental to Chinese society and values. This perception further compounds the stigmatization of homosexuality, associating it with undesirable Western ideologies.

Therefore, the nationalist rhetoric identifies homosexuality as a threat to national identity and social cohesion, reinforcing the notion that it is a foreign or Western concept. Consequently, the phrase “daughter that lives a Westernized life,” after gaining prominence, has been shortened to “Westernized daughter,” broadly categorizing homosexual women and becoming a more visible target for anti-western sentiment in mainland China. Implicit within its usage is a subtle commentary on the perceived clash between traditional values and Western influences; the syntax has been carefully chosen to target those who are queer and imply that their lifestyle is Westernized, which is also linked to openness, inclusiveness, and freedom of expression that is connected with the LGBTQ+ community. In addition, it can be seen through Janovicek’s writing arguing that often Western governments are the ones that possess legislation aimed at safeguarding the rights of queer individuals [10]. Hence, the CCP's stance contrasts with that of Western governments, suggesting that homosexuality is a foreign concept that could potentially endanger the Chinese nation.

Furthermore, Xie and Peng’s study in 2013 found that 78.53% of Chinese respondents believed that “same-sex sexual behavior is always wrong”[11] and suggested that the attitudes towards homosexuality in mainland China are conservative and less tolerable. Additionally, the large percentage suggests that many people are unaware of the presence of homosexuality in mainland China, evident from the reasons given, with one of them being homosexuality clashes with the traditional Chinese culture of polygamy and heterosexualism. Therefore, when homosexuality is openly shown in Western cinema, the movie is not even allowed to be released in China due to its inclusion of homosexual content [12].Thus, homosexuality can be a shocking fact for many, as they fail to recognize the legitimacy and agency of LGBTQ+ people, some of which could be their children.

The prohibition or censorship of explicit terms such as "homosexual" or "lesbian" on various social media platforms further complicates the challenge of visibility, relegating LGBTQ+ identities to the shadows of the public sphere [13]. Especially lesbians in Communist China find themselves negotiating a delicate balance between their identities and the prevailing nationalistic discourse. In this landscape fraught with tension and ambiguity, queer individuals, particularly lesbians, find themselves traversing a precarious path of self-discovery and self-affirmation.

The concealment of the lesbian identity from China News is symbolic of the avoidance from the State; individuals often feel unsafe and experience a double marginalization from the government’s strangling policy and negative societal attitude [14]. In Cheng's study on lesbians’ lived experience in Mainland China, an interviewee states that