The earth is flat. Not metaphorically as in Thomas Friedman’s best-selling book about globalization, but literally so, according to rapper BoB and other “flat earthers”. They are a tiny minority. But they are out there, millions of them.

One might, indeed, think that in the 2020s anything goes. Facts seem to matter little and can always be countered with simple “whataboutism”. You can find a distraction to virtually any issue, from the need to combat climate change (what about jobs and economic growth) to the necessity of alleviating the hardship of refugees (what about “our” values). Forever gone is a simpler age when the world was divided into two ideologically opposite camps that stood for clearly identifiable notions about governance and modernity. Sure, the Cold War propagandists oversold their versions by manipulating facts. But at least there was some regard for facts. In today’s “post-truth era” it seems that disinformation is the only game in town.

But has everything really changed in the last three decades?

Cold War propaganda essentially amounted to “campaigns of truth” or battles for the hearts and minds of people based on a simple binary choice. On one side, Americans heralded the virtues of democracy and free markets while painting a dark picture of communist oppression, a system of total state control that stifled freedom at all levels. On the other side, the Soviets championed social justice while emphasising the devastating consequences of inequality resulting from capitalism.

The effectiveness of both American and Soviet propaganda, however, was based upon relative truth: there was no denying, for example, that individual freedom was poorly valued in the Soviet bloc. Equally, poverty and homelessness were visible reminders of the downsides of the capitalist system. Effective Soviet and American propaganda did not require its propagators to invent facts, merely to highlight the convenient ones.

The end of the Cold War implied the end of the ideological East-West binary. But rather than reflecting an end of history and the dawn of a liberal consensus, the last three decades have seen an increasing number of new divisions that are not connected to a dominant ideology or grand narrative. Terms like “the free world” (or pretensions to its leadership) have lost their resonance.

When combined with the rapid development of easily available digital resources and social media, the end of an ideological binary has created a world in which recognisable soundbites are all that counts. As attention spans have diminished, complexity has disappeared. More actors, more outlets, and more freedom of expression translate into a situation where taking control of as much of the public space as possible is the only thing that matters. Donald Trump’s success in American politics was, after all, largely based upon his ability to occupy the centre of every conversation. But aside from banal slogans, a dominant personality and hurtful nicknames for his opponents, did Trump have a core message? Doubtful. If anything, his strategy relied on obscuring facts by promoting misinformation and spreading conspiracy theories.

But what is really new here?

The difference is not that binaries as such are gone. There is a natural tendency among people towards division on almost any issue. Take NATO, one of the enduring institutional bedrocks of both the Cold War and post–Cold War international system. NATO has been riven with internal tensions and disagreement throughout its long history. The alliance was declared obsolete many times before Donald Trump used it as an example of how European “free riders” had benefited from America’s benevolence. But NATO survived Trump’s rhetoric, gained an extra member state (North Macedonia) and is considered, today, as indispensable as ever.

The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (that very “special military operation”) on NATO is obvious. But the invasion has also highlighted the disturbing realities of the post-truth era we live in. All kinds of narratives have emerged or been floated to justify or complicate the simple fact that one country invaded another. None has been more popular and influential than justifying Russian invasion with NATO enlargement: Russia simply acted in pre-emptive fashion to prevent NATO countries from their aggressive enlargement.

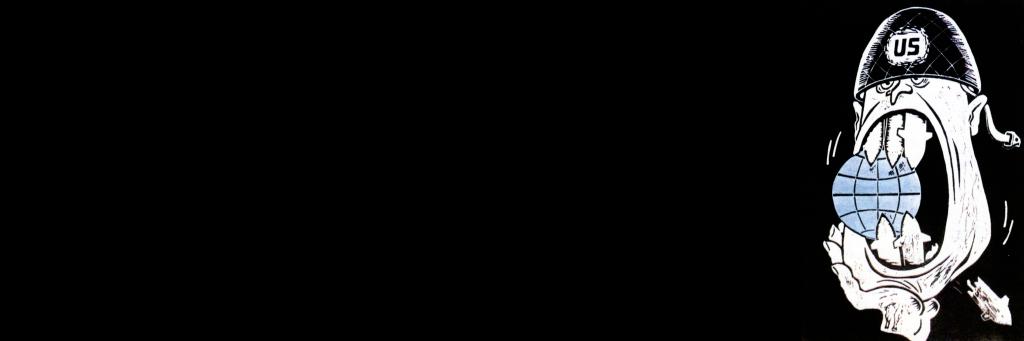

Such a narrative represents an example of the post–Cold War media strategy by a state actor (Russia) that is simultaneously traditional and novel. It effectively resuscitates a Cold War mindset by elevating Russia – much like the Soviet Union – into a position of counterweight to “the West”. Its success, however, relies not on pointing out social inequities as was the case of Soviet propaganda but on the hypothetical and conspiratorial notion that the United States is out to conquer and dominate. In our post-truth era there is no need to provide facts. The accusation itself, constantly repeated, will suffice. It will certainly divert attention away from what may, for Russia, be uncomfortable facts.

It seems that the simple act of questioning and disagreeing has become the modus operandi in the age of social media and the internet. It is difficult to imagine that there are any facts that will remain uncontested, or any beliefs that can be contested without repercussions. Facts have become relative and beliefs have become absolute. Which raises the stakes for anyone who still suspects that the world may not, after all, be flat. Happily, they remain the majority.

This article was published in Globe #31.

GENEVA GRADUATE INSTITUTE

Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2A

Case postale 1672

CH - 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland

+41 22 908 57 00

ADMISSIONS

prospective@graduateinstitute.ch

+ 41 22 908 58 98

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

sophie.fleury@graduateinstitute.ch

+41 22 908 57 54

ALUMNI

carine.leu@graduateinstitute.ch

+ 41 22 908 57 55