Ágnes Heller transformed her life through a troubled 20th century into a life of reflection that never shied away from raising her voice against injustice : ‘I lived through terrible things. But I had to understand them. […] Philosophers do not despair.’ Shalini Randeria and Ludger Hagedorn honour her legacy on her birthday with a text published by Eurozine.

What was so paradoxical about Europe that Ágnes Heller gave the last book published in her lifetime the German title “Paradox Europa”? Her answer: Europe has a blind spot precisely where it boasts most vocifourously of its own achievements.

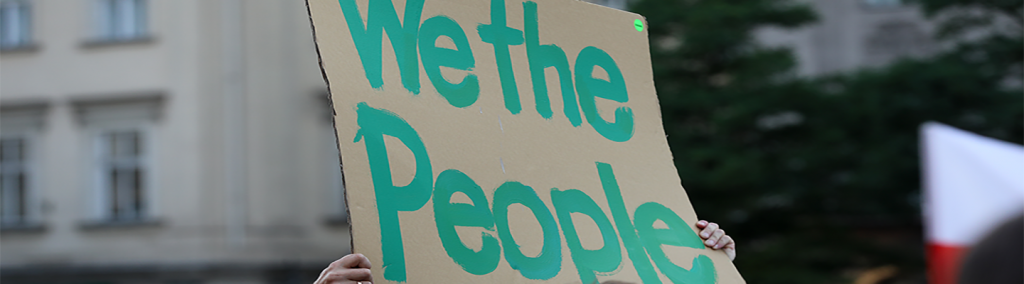

These are achievements from the Enlightenment, which have granted inalienable rights to each individual and made emancipation possible in Europe. The bearers of this promise of rights are the various nations. And so, from the beginning, there was tension between the universality of human rights and the exclusivity of citizenship rights. While the former belongs to everyone in the world, the latter is only granted to the citizens of a particular nation.

The first European nation, France, ‘la Nation’, was also the first country to guarantee such rights. But which individuals were, and are, protected by its constitution? It is a constitution for both ‘human beings’ and ‘citizens’. And therein lies for Heller the crux of the matter. From their inception, universal human rights have been linked to national citizenship rights, granted to all citizens of a country regardless of gender, religion or class, but they exclude foreigners and migrants. This distinction between “human beings” and “citizens” often does not come into play and may even seems trifling. But as soon as things ‘get serious’, as Heller puts it, a conflict arises in which historically ‘humanity has almost always been on the losing side’.

The consequences of this crucial difference are serious. One consequence is the attitude and identity of the individual themselves. When problems arise, which individual identity proves to be stronger? The exclusive, national identity on which citizenship rights are based, or our universal identity as bearers of human rights? History tells us that ever since this tension first arose, it has been resolved all too often and all too firmly in favour of citizenship rights and to the detriment of human rights.

Ágnes Heller does not mean to condemn national identity. She takes a realistic, unsentimental view of the matter – nations are simply a given. Moreover, as human beings, we are not born into ‘the’ world but into a ‘particular’ world with a specific language and community that confers security and belonging. This is what Heller calls the ‘basic anthropological attitude’.

Read the full article on Eurozine website

The Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy collaborates with Eurozine, an online magazine and European network linking up more than 90 cultural journals and associates in 35 countries.

Read more opinion articles and media interviews of Shalini Randeria:

08 May 2020 – Das Magazin, Armes reiches Indien

30 April 2020 – IHEID, Defending Press Freedom in the Time of Coronavirus

25 April 2020 – Die Zeit, Darf der Corona-Impfstoff patentiert werden?

28 March 2020 – Die Zeit, Globalisierung: Die Heimatlose

16 March 2020 – RTS, Interview on India’s new citizenship law