How and why did you choose to study the relationships between Japan and South Korea in the light of transitional justice?

I developed my passion for researching on Japan while spending last year’s semester in Tokyo, as part of my Master’s programme. During that time, I had the chance to not only learn about and visit Japan’s historical and cultural heritage, but also travel to South Korea for a short one-week trip. These experiences sparked my desire to understand the historical tensions shaping the diplomatic relations between the two countries, ultimately leading me to the topic of my dissertation.

What were your research question and methodology?

I started wondering whether transitional justice, as a multidisciplinary framework for addressing systemic human rights abuses and fostering reconciliation, could be applied in contexts that went beyond its normative conception of achieving democratisation. With the invaluable help of Professor Maria Neus Torbisco Casals, my thesis advisor, I thus started structuring my thesis by investigating how measures of transitional justice could contribute to the long-term reconciliation of diplomatic bilateral relations between Japan and South Korea. The goal I had in mind was to demonstrate that an application of transitional justice in well-consolidated democracies was not only possible but favourable for the societies wishing to address their past historical evils.

Using the comfort women dispute as a case study, I applied a sociological and historical analytical lens, conducting in-depth library research and a comprehensive literature review.

And what did you find?

I found that, in the context of the comfort women case, for interstate reconciliation to happen, the two countries had to agree on shared visions of truth, responsibility, national memory, and historical narratives.

Transitional justice – a framework traditionally confined to postconflict or transitioning societies – can be effectively adapted to reconcile interstate diplomatic relations in well-established democracies. While the research did not aim to simplify or resolve the reconciliation process between Japan and South Korea, it highlights the potential of truth-telling, reparations, and collective memory as measures to foster a shared historical narrative and address the structural injustices of the past. Of course, up until this point, this research provides a theoretical pathway for diplomatic reconciliation between two countries. It would be fascinating to see these ideas applied in practice. Perhaps I will have the opportunity to develop this work further in the future!

What are you doing now?

Currently, I am working as a young professional in the Research & Analysis team of the NGO CyberPeace Institute, exploring the impact of cyberattacks and disinformation in the international sphere while advocating for responsible behaviour in the cyberspace. Next February, I will relocate to Paris to start working with the Asia and Pacific Unit of UNESCO – an opportunity that will allow me to keep expanding my interest in the Asian sphere! Looking ahead, I wish to pursue a career in humanitarian aid, diplomacy and peacemaking, emergency preparedness, and crisis reduction, continuing to explore ways to promote peace and justice on a global scale.

* * *

How to cite:

How to cite:

Cardillo, Maira. Transitional Justice between Consolidated Democracies.

Graduate Institute ePaper 55, Graduate Institute Publications, 2025.

https://doi.org/10.4000/132hs.

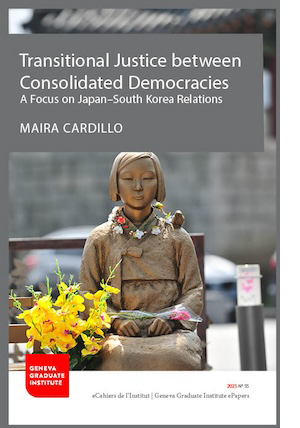

Banner picture: Shutterstock/Pvince73.

Interview by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.