As the monsoon continues to strike several states in India, millions of residents face not only devastated homes and landscapes due to extreme flooding or drought but also frustration, fear and hopelessness.

Residents living along the India-Bangladesh border have a long history of being considered “foreigners” in India, and my doctoral research demonstrates their centrality in understanding the state today. India as a political and bureaucratic apparatus and as a social process is working to homogenise borderlands with a goal of shaping of national identity.

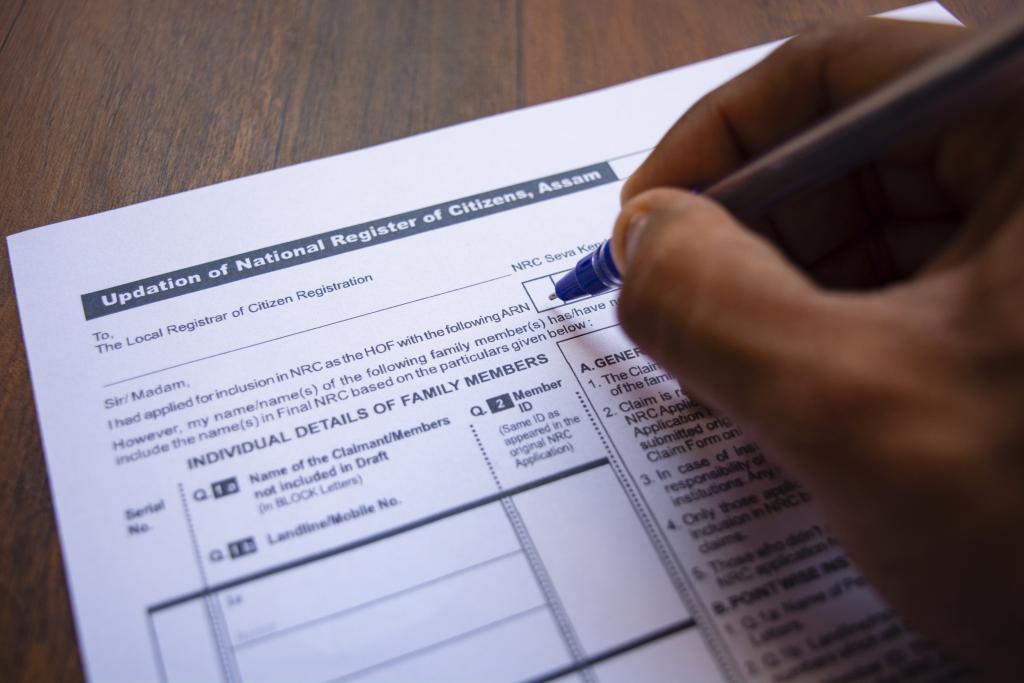

The final list of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), created in 1951 and which registers all identified as “genuine citizens”, is expected to be published on August 31 for the state of Assam along the India-Bangladesh border. It will decide upon the future of millions of people in the state.

Why is this register crucial to understanding the way Indian politics are going today? What can it tell us about citizenship and identities, and how will it affect thousands of people in the South-Asian region?

Unwanted people

In the last four years, the right-wing Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been particularly vocal about ridding the Indian territory of “Bangladeshi infiltrators”.

Assam became a starting point following prevalent “anti-infiltrator” sentiments in the state. Agitators demanded that the 1951 NRC – conducted for the entire country – be updated. It led the Indian Supreme Court’s order of 2014 in directing the government to update the NRC in the state of Assam.

The final draft of Assam’s updated NRC was approved on 30 July 2018. It now classifies as an illegal immigrant and foreign national any individual who entered the state after March 24, 1971.

More than 31 million people in Assam have since had to prove their Indian citizenship. Last year, four million found out that they would no longer be considered Indian citizens. Closely following the draft publication, on 29 August 2018, the state of Assam was declared a “disturbed area”, with the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), being extended for another six months.

It brought the entire state of Assam under the rule of the security forces, giving them special rights and immunity in carrying out operations. The whole state remains under AFSPA, making ordinary people vulnerable to the power of the security forces.

Sorting out human beings

On 17 July 2019, the Indian Home Minister, Amit Shah, who belongs to the BJP, announced in the upper house of the Indian parliament that the government will identify illegal immigrants staying in any part of the country and deport them as per international law.

These pronouncements sound like the trumpet of Kafka’s The Departure, an indication from political leaders to the settlers in Assam, many of whom are now being recategorised from Indian citizens as “illegal immigrants”.

The NRC process and lists have been considered highly questionable and erroneous, which explains the delays in finalising and publishing the final draft.

Nearly four million people, constituting 12.5% of Assam’s population await the final verdict. Many will face an uncertain journey that may very well lead them to life-long exclusion and marginalisation.

As soon-to-be non-citizens, they will be removed from the voters list and expropriated. Many may end up in jails and detention centres that are being built in Assam, according to media reports.

Instilling national fear

Right-wing politics around the globe have been shaping a political narrative of “national fear”, identifying names and faces of the unknown “infiltrator”. In this scenario, created to politically control immigration, “foreigners” and “nationals” are increasingly being determined by their bloodline.

Assam experienced migration from the 19th century onwards, from the neighbouring regions of Bengal, Jharkhand, East Bengal (which later became East Pakistan and then Bangladesh) and Nepal, among others. Census data from 1901 till 1971 shows large polulation movement from East Bengal to Assam, but a drop in population growth since the 1971 creation of Bangladesh.

The creation of the India-East Pakistan border in 1947 transformed the easy movement of settlers in the Bengal delta into international migration. Millions of Hindus moved from East Pakistan to India and Muslims moved from India to the newly formed East Pakistan. In 1971 it took the name of Bangladesh. These movements took place in waves. The narrative of homecoming identified new settlers under many labels: political migrants, repatriates, refugees and displaced persons. It blurred the distinction between “political” and “economic” settlers.

As Willem Van Schendel points out, the border was instrumentalised in fuelling the anti-migrant settlement argument. It also nourished the Indian narrative of “infiltration”. The argument gained traction when it was discovered that many recent immigrants from Bangladesh were Muslims. It empowered the claim of Hindutva politics that such movement was a threat to Hindu India as it pegged Bangladeshi infiltration as a national issue.

Since the early 1990s, such framing has led to many Bengali-speaking Muslim migrants in the Delhi region being rounded up on the suspicion of being Bangladeshi. Many were illegally deported to Bangladesh or simply held under duress by Delhi police.

The Bangladeshi "infiltration" and Assam

As Professor Debarshi Das has observed in his 2019 book, The Saga of Assam’s National Register of Citizens (NRC), (People’s Study Circle, Kolkata):