Introduction

Often labelled by official accounts as “the revolution in the revolution,”[1] the social changes brought about by the Cuban Revolution (1953-1959) mark a critical juncture in women’s reproductive rights history. Although Cuba formally gained independence from Spain in 1898, the Cuban Revolution reads as a direct response to many years of continuing foreign interference and control. Framing decolonisation as non-domination,[2] the Revolution offers a unique case to examine the gendered dynamics of nationalist struggle. The changes implemented by the patriotic movement that drove the Revolution had far-reaching implications for women’s rights, as nationalist objectives joined with advances in general and reproductive health. By analysing the impact of the Cuban Revolution on women’s reproductive rights and autonomy, we gain deeper insight into the broader dynamics of gendered politics in postcolonial societies. Ultimately, Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) prioritised anti-imperial liberation over women’s emancipation, essentially constructing women’s reproductive bodies as national assets.[3]

Foreign Domination and Resistance in Cuba

Decolonisation as non-domination can be understood as the anticolonial (re)making of a global world order, free from colonial hierarchies and both direct and indirect economic or political control.[4] This perspective emphasises dismantling formal colonial rule as well as subtler forms of dominance that persist through economic, political, and cultural ties.

According to some Cubans,[5] Cuba’s decolonisation journey began with forms of anticolonial resistance throughout the period of Spanish colonisation between 1511 and 1898. The subsequent United States (U.S.) victory in the Spanish-American War led to the United States’ occupation of Cuba from 1898 to 1902. During the occupation, the U.S. imposed the Platt Amendment unilaterally, creating the legal foundation for its repeated interventions in Cuban affairs in the years to follow.[6] The U.S.’s geopolitically motivated support for the authoritarian coup by Batista in 1952 exemplifies its neocolonial dominance.[7]

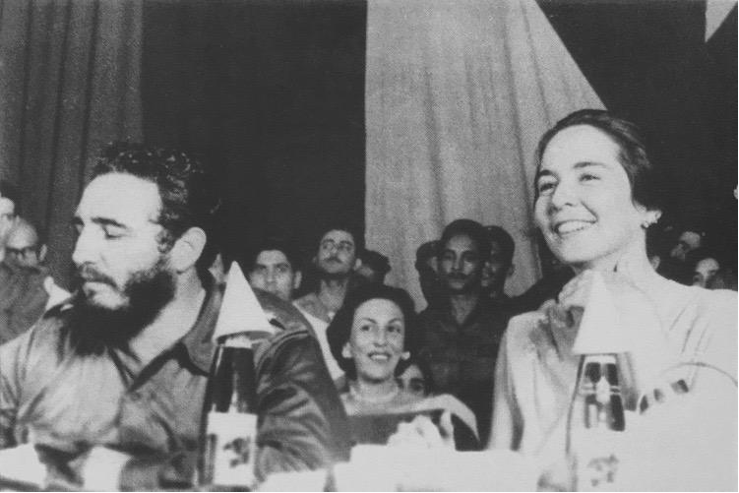

The M-26-7 movement originated in Havana in 1952-1953 in response to the establishment of the dictatorial regime. In this movement, students and workers mobilised around Fidel Castro and other revolutionaries such as Vilma Espín and Celia Sánchez (see Figure 1). The Cuban Revolution began after their initial failed attack on the Moncada Barracks on July 26, 1953. This attack was led by revolutionary fighters, including Haydée Santamaria.[8] The movement was named after this attack.[9]

After the attack, Fidel outlined his ideas in his “History Will Absolve Me” speech during his trial. Addressing Cuba’s dire socio-economic conditions, he proposed five revolutionary laws to restore democratic governance, grant farmers land ownership, let sugar and industrial workers share in production profits, and confiscate the assets of corrupt officials. In this speech, Castro reduces women to “those entrusted with the sacred task of teaching our youth” (alongside young men).[10]

In 1955, Fidel and other revolutionaries were granted amnesty. They went into exile in Mexico, where they met Che Guevara and returned together to Cuba on board the Granma in November 1956. Losing many fighters upon arrival, the revolutionaries regrouped in the Sierra Maestra mountains and waged a guerrilla war against the Batista forces in 1957 and 1958.[11] After the decisive Santa Clara battle in December 1958,[12] Batista fled Cuba on January 1, 1959, marking the end of his regime and the beginning of post-revolutionary Cuba.

The Revolution initiated substantial societal changes as a response to many years of foreign domination. Although these changes were aimed at national autonomy, they significantly affected women’s reproductive rights. As such, Cuba’s decolonisation journey and the Cuban Revolution provide essential context for understanding gendered critiques of nationalism.