Thank you very much for sharing such a personal story. By listening to you, I think that we can get an idea of the atmosphere of Germany during that period, and in particular, this need to participate in the reunification of the country.

Achim, your position as an “actor” of history puts you in a very original position – you understand this event as both a participant with subjective experiences, while at the same time, you contend with it on the level of a professional historian. How do you think a historian such as yourself should deal with personal experience? Should you detach yourself from it? Or should you rather plunge into your feelings and memories?

Thank you. Perhaps it is too gratifying to be called a “historical actor”. I think that as a student of history, one should keep a distance from that “micro” experience in order to better grasp the events – if you want to zoom out and have a bird’s eye view.

I think you should neither detach yourself nor plunge into your feelings and memories. It is in combining the memories and the literature that you will have the whole picture. In this sense, the only difference is that you have lived during that time, and the closer it remains, the more accurate could it become. At the end of the day we are limited generational human beings.

Moreover, we tend to interpret events in a context that is always different from the past. That is why I think we do not know better, for example, the history of the Roman Empire today than perhaps our scholar ancestors thousand years ago, when the first universities appeared and when Latin was the lingua-franca used among them.

So Achim, let’s continue and dig further into your experience to extract the main concerns of the German people in 1989. How would you describe your perception of the socio-political changes that were happening in Germany? Were you aware of the historical impact of the fall of the Berlin Wall?

At the time I was just a teenager, and all the fuzz of the Cold War politics and the Soviet Union itself were a distant story that I did not consider. At the time, the main priority was to take down the Berlin wall; it was the reunification of Germany.

The concept of Einheit und Freiheit, (unity and freedom) the historical German question of the German people was still on the table after many years, since the partition of Germany after World War II. Even West Germany’s first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, in reality, never thought that Bonn was really the capital of Germany; it was considered as a provisory seat.

The wall represented, therefore, that physical impediment dictated from the two superpowers over Germany, against that German concept of unity and freedom.

One needs to understand that in the context of the previous historical settings, before World War II, in the German mind, the Weimar Republic represented an achievement compared to the imperial period. But it was the dichotomy between cultural flowering and the political disorder that also characterised Weimar, leading to the immoderate politics of the thirties.

Hitler, therefore, came at a specific time and with a particular mission to establish German unity – at home and with those abroad – and to reply to the Versailles humiliation with a Grössdeutsch lösung. Hitler’s geopolitical ideas and policies, from a German point of view, tried to preserve the European balance of powers, while extra-European powers were condemning Germany to mediocrity and, ultimately, all of Europe to external domination – which in fact, after World War II, really happened.

Connecting this situation during 1939-1941 to the situation of the Cold War and the agitations of the last months of 1989, it was beyond my scope of just hammering down the wall. Frankly, it was not even about democracy in the [German Democratic Republic] GDR. In fact, if you look back, whether the GDR was a democracy is a controversial issue, and that is why several “Ossis” (Germans originating from the Eastern part) still today feel nostalgic about the GDR, and even about the social system.

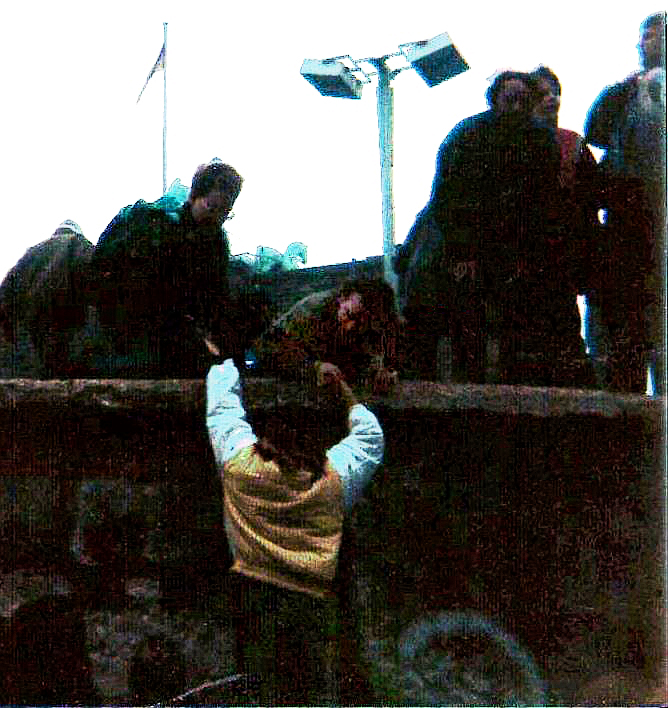

Anyway, as I said, in 1989 I was in Berlin just for freedom and unity, and that was clearly wished for and shared on both sides of the wall. In other words, yes, there was a wish to change and destroy that chain that was represented by the Berlin wall. But that this later went on so far to change the whole international context – the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet Union and even the end of the Cold War – I was not really thinking about it. This can only be seen now, from a distance.

How about now? How do you understand your experience after almost three decades have passed?

Now, after all these years, I feel I was indeed part of that popular enthusiasm that was able to challenge a rigid geopolitical system, at least for Germany. But at the same time, we should not forget that the ground was prepared for that.

The “wind of change” was already blowing in the previous years, and I remember Gorbachev with his perestroika programme to rescue what was basically left of the Soviet Union.

Right or wrong, many people in Russia have accused Gorbachev of instigating the collapse. Perhaps perestroika and glasnost were just a solution to postpone an evident disintegration of the Soviet system, but instead helped to accelerate it. But it was part of a longer process that can be seen by looking into the internal political struggles within the Soviet Union itself.