How does a long historical view of China’s relationship with the Vatican help understand cultural representations and “misunderstandings” that you discuss in the article?

The ruptures between China and the “West” (a term referring historically to Europe, but that today would include the United States) are rooted in the Enlightenment. China had a healthy dialogue with Renaissance Europe, particularly Italy, and its European interlocutors were often Jesuits. Jesuits were pioneers among European travellers: unlike travellers such as Marco Polo and others, who had a limited experience of submerging themselves in the Chinese sociocultural world, Jesuits had actually lived in China and were intellectually and culturally engaged there. By recognising the Chinese way of governance as effective and rational, they represented the Renaissance view of China. This did not fit into the Enlightenment model of governance, which employed a racial and civilisational hierarchy that upheld Western rationality as superior and represented China as a backward, feudal and morally corrupt society governed by “Oriental despotism”. Thus, in the Enlightenment tradition, the willingness for accommodation and adaptation of Christianity to local Chinese contexts was limited, and “Western” values preached through Christianity were seen as “necessary” impositions.

You draw a comparison between the 17th-century Chinese Rites Controversy and contemporary debates about China. Can you explain it?

The Rites Controversy, which spanned a long period of time – from 1645 to 1742 –, was about the decisions on the rites, terms and sites of Christian worship in China. It exposed the tensions between Chinese Confucian practices and other traditional rituals such as those honouring ancestors, and the Church’s insistence on the Chinese converts’ adherence to more rigid Christian tenets that were being suggested. The earlier period of Jesuit engagement had been of one of accommodation, and this had become the basis for a split within the Catholic Church. Catholic theologians attacked Jesuits for distorting Christian values by claiming that Chinese rituals were compatible with them. Ultimately, as a result of the controversy, the Vatican decided against the Jesuits in 1742, prompting the Emperor of China to cut official links with the Vatican. The political ideology emerging from the Enlightenment was becoming “anti-Chinese” in character and had departed from the Jesuit model of “virtuous governance”.

Today’s Western debates about China are comparable to aspects of the Chinese Rites Controversy. Cultural and racial prejudices, coupled with the use of post-Enlightenment Western values and conceptual frameworks – for instance the discourse on “democracy”, “individualism” and “personal freedom” – have similarities with the Controversy debates. This line of reasoning does not recognise the Chinese model of governance and its potential for success except through the idea of Western “rituals of governance”. The idea of Oriental despotism still persists, along with the view that it is only by imposing Western values that China can progress.

What do you think of the potential reconciliation between China and the Vatican, and the role of the latter in the international arena?

The opportunity for serious cultural dialogue was historically ruptured in the mid-18th century. The Vatican could be an important interlocutor to restart the cultural dialogue with China and accommodate diverse interests. There are deficiencies and shortcomings in the Chinese system, especially the influence of the “Bolshevik”-style organisation. But for the way forward, “accommodation” here means negotiating without viewing Western powers in a superior position of negotiation. The Vatican may be a key helper in this conversation. A Jesuit has become Pope for the first time, and Jesuits have been the vanguard of Christian missions in non-European worlds, with a long history of flexible and accommodative approaches to religion and culture.

In the early 1950s, during the Cold War, China had cut off relations with the Vatican. Since the end of the Cold War, the Vatican has sought to expand the influence of the Catholic Church. China is still “untapped” territory where the Catholic Church has limited official influence, despite a fairly large population of Catholics. Now, there are more pragmatic, accommodating responses from the Vatican in dealing with the question of Catholics in China. Here, accommodation relates essentially to who chooses the bishops. The Communist regime cannot be prevented from having a say on these appointments, which the Vatican now is willing to acknowledge, pursuing a non-dogmatic approach towards the issue. The Vatican has had some positive experiences of dealing with Communist regimes, such as Vietnam for instance. Pope Francis and the Vatican understand the significance of the recent “rise” of China differently from countries like the United States, who sees this phenomenon in competitive and rivalry terms. The Vatican has been one of the best-informed regimes historically, and unlike contemporary governments which come and go, the continuity of its long-term visions fits with China’s perspective.

* * *

Full citation of the article:

Xiang, Lanxin. “China and the Vatican.” Survival 60, no. 3 (2018): 87–94. doi:10.1080/00396338.2018.1470757.

* * *

Interview by Aditya Kiran Kakati, PhD candidate in International History and Anthropology and Sociology. Editing by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.

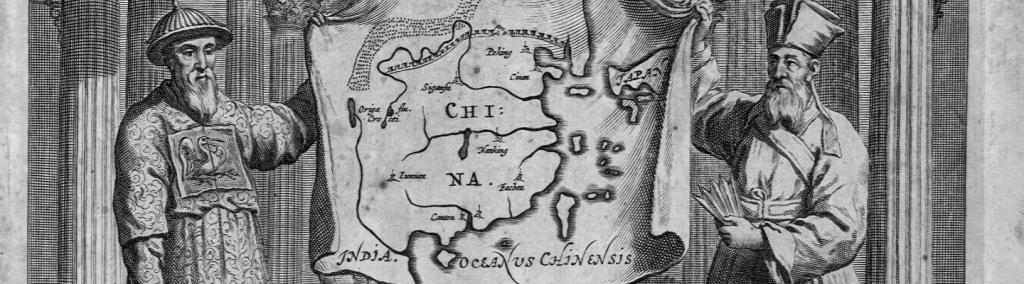

Banner image: Athanasius Kircher [CC BY 2.0].