What exactly is the APSA?

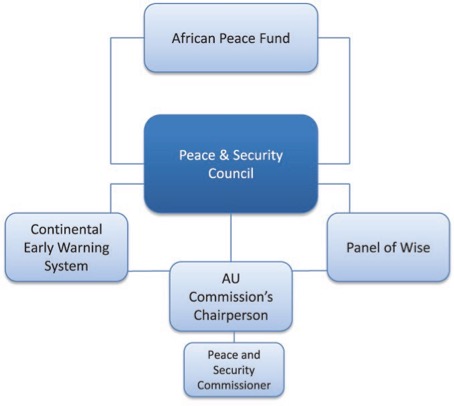

The APSA – African Peace and Security Architecture – is the continental framework launched by the African Union in 2002 and dedicated to promote peace and stability in the region:

It is designed as a system of institutions, norms and policies, whose threefold purpose is to deal with conflict dynamics, tackle security challenges and promote sustainable development on the continent.

At the time when the Organization of African Unity was transformed into the African Union (AU), the latter has embedded its will and commitment to play a key role in peace and security on the African continent and beyond. To this end, the APSA was created on the basis of “non-indifference” (see Article 4 of the AU Constitutive Act) and in the spirit of pan-Africanism (see Article 12 of the “Solemn Declaration on a Common African Defence and Security Policy”). The idea of African ownership of peace and security on the continent was an important vision of the African Union clearly expressed through the APSA, and deeply connected with the regional integration project.

What are your conclusions about APSA’ achievements in promoting peace and security on the continent?

It’s important to mention how the AU, in the framework of the APSA, approaches the concept of peace based on endogenous context and values. Indeed, the AU considers peace in a comprehensive perspective, as illustrated in Agenda 2063 by its vision for “an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens representing a dynamic force in international arena”. One of the novel principles introduced by the APSA is the right of the AU “to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity” (in Article 4 of the AU Constitutive Act). This was an important novelty as it provided a legal basis for the intervention of the regional organisation with a view to resolving interstate disputes and internal conflicts that Africa often faces. As such, it reversed, at least in principle, the primacy of state-centric rules, formerly embedded in OAU’s Charter. In 2015, the political crisis in Burundi gave rise to the first instance of the African Union’s Peace and Security Council authorising the deployment of 5,000 African peacekeepers in the region. Even if this initiative was not completely successful, due to the severe obstruction of the Government of Burundi, it provided an opportunity to mitigate what could have been a terrible civil war.

Besides, the AU launched in May 2013 a flagship initiative called “Silencing the Guns”, whose main purpose was to promote peaceful resolution of wars within the region and contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as reinvigorate the spirit of pan-Africanism and the African Renaissance. In relation with this initiative, the APSA’s Panel of the Wise (PoW) represents a pioneering institutional innovation. Indeed, the PoW is a relevant component of the APSA as it is based on the African tradition of mediation entrusted to elders. It includes five prominent African leaders, and can act on its own initiative. During the last decade, the PoW contributed to solve several conflict situations in the region.

Does the “African solutions for African problems” doctrine remain an appropriate solution for the future?

The debate on “African solutions for African problems” remains relevant in relation to the promotion of regional peace and security strategies. Actually, this approach dates back to the independence period and is deeply connected with the project of regional integration. During the 1960s, African leaders advocated the policy of “Try Africa First” to deal with peace and security issues on the continent (see Andemicael’s The OAU and the UN), given that the leitmotiv of African ownership was strongly linked to the pan-African project. I’ve said earlier how “non-indifference” and pan-Africanism are foundational to the APSA. Furthermore, in 2004 the African Heads of State and Government stressed in the above-mentioned “Solemn Declaration” the need to develop and promote endogenous policies for peace and security on the continent. The objective here is to demonstrate ownership by providing proper and rapid responses to peace and security challenges in the region. Regarding this purpose, the doctrine remains pertinent. However, it faces the critical issue of resources.

How so?

The establishment of the APSA represents a major stage for peace and security process in Africa as a shift from a traditional non-interfering orientation toward a more interventionist approach. However, how can the APSA promote “African solutions for African problems” without its own resources and resulting autonomy? Indeed, it suffers from a serious financial dependence, which leads to a complex relationship with its external partners. The APSA is still largely funded by external regional and global institutions, particularly the European Union. For example, African Peace Support Operations have been traditionally funded through the African Peace Facility, which was established by the European Union (EU) at the request of the AU. AU–EU relations reflect how complex it is for the former to achieve its ambitions without strong autonomy. Even if both organisations attempt to break free from the traditional donor-recipient model and promote genuine partnership, the issue of funding would undoubtedly generate inequalities between the two institutions. Certainly, the financial relations of the AU with its external partners call into question the reality of the very idea of African ownership put forward during the creation of the APSA. At the AU Summit in July 2016, the rule of 0.2% levy on all acceptable imported goods on the continent was agreed upon, so that the AU could finance 100% of its operational budget from 2017 onwards. Unfortunately, this objective remains a theoretical ambition.

In spite of its weakness, however, the APSA offers a fine illustration of how peacebuilding initiatives are approached in Africa, beyond a classic understanding of peace as absence of war. At a practical level, the AU has to translate this vision into concrete policies. Agenda 2063 notably identifies the following main goals to be achieved:

- A prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development

- An Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law

- An Africa whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential offered by people, especially its women and youth.

Thus, the AU emphasises the necessity to consider peace beyond the focus on power politics and the peace-security nexus. By doing so through APSA, it aligns itself with the SDGs. In the same way as the UN, it has placed its peoples at the core of its purpose, as the raison d’être of its commitment.

* * *

Full citation of the chapter:

Degila, Dêlidji Eric, and Charles K. Amegan. “The African Peace and Security Architecture: An African Response to Regional Peace and Security Challenges.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Approaches to Peace, edited by Aigul Kulnazarova and Vesselin Popovski, 393–409. New York: Palgrave, 2019.

* * *

Interview by Marc Galvin; editing by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.

Banner image: 2013_01_29_MGD_Engineers_Clearance k by AMISOM Public Information, licensed under CC0 1.0.