In August 1945 Herbert Lehman, the American Director General of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) – an organisation set up to help with economic reconstruction of war-torn countries in Europe – professed at one of the agency’s meetings: “Seed is the most compact form of potential food value. The yield of grains runs around twelve times that of its seed. For peas and beans, the ratio is less but, for most vegetable seeds, it is much greater. One-fourth of a pound of cabbage seed will plant an acre of land to produce some 15 to 20 thousand pounds of cabbage. Seeds offered to starving peoples in Europe and China by the uninvaded countries are producing and will continue to produce the food that will eventually conquer hunger as the armies of the United Nations have conquered the foe”.

Lehman’s statement coincided with the beginning of UNRRA’s shipment of tractors, seeds, draught animals, pesticides and fertilisers to Europe. Following Hitler’s defeat in May 1945, UNRRA cargoes carrying up to 70,000 bags of seeds left from US and Canadian Ports and by the end of the same year an estimated total of 38,000 metric tons of seeds had been shipped to Greece, Yugoslavia, Albania, Poland and Czechoslovakia, some of the countries receiving full scale UNRRA aid.

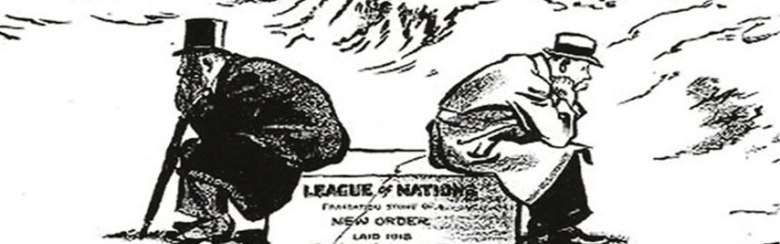

Food and agriculture have always been at the heart of the development narrative. From the late nineteenth century onward, scientists, diplomats, experts and bureaucrats sought to confront social, economic and scientific challenges arising from the globalisation of agricultural trade and production. The two World Wars rendered the importance of food security and the need for improving the social and economic conditions of rural communities more visible, encouraging government and institutions to respond with top-down development programmes. Various recent studies have focused on the interwar and immediate post-war years as a crucial period for understanding the agrarian transformations that occurred in the second half of the twentieth century.

The full role of wartime relief agencies and early post-war international organisations in the circulation of agricultural expertise, knowledge and technology, and its impact on food production and food systems, however, remains yet to be researched. For historians, the archives of UNRRA open a window into the rationale and implementation of so-called ‘agricultural rehabilitation’ measures and their echoes for current agricultural development programmes. As historian Curtney Fullilove has recently remarked, “seeds are powerful signifiers

because they compress future potential and deep past into objects both minuscule and abundant.” Given their role in largescale biological processes accompanying cultivation, migration and colonial expansion, seeds, as Fullilove argues, often come with metaphors of invasion, wars and conquest.

In recent years, historians have questioned the implied biological determinism of such language and produced more fine-grained analyses of how crop transfers in the twentieth century were embedded in political, scientific and economic processes. Indeed, the last two decades have seen a number of fascinating historical studies that zoom in on specific crops and commodities, such as sugar, rice, soy, cotton against a backdrop of colonial and global governance, capitalist consumption patterns and agricultural knowledge transfer. In addition, recent historical work on the political and scientific engineering of non-human organisms offers tantalizing insights into the relationship between agriculture, science, and technology.

To trace the shifting and contested meanings of international agricultural development discourse and practice, the historian builds on a multi-archival and transnational historiographical approach that focuses on the circulation of people, ideas and goods.

Another historian of agriculture, Deborah Fitzgerald, points out, however, that understanding the relationship between technology and agriculture is not only about technology as a set of objects (tractors, milking machine, pesticides, seeds etc); it is also about “understanding the institutions, individuals, ideas and practices behind the objects.” It is here, maybe, that the role of the historian is most required. To trace the shifting and contested meanings of international agricultural development discourse and practice, he or she can build on a multi-archival and transnational historiographical approach that focuses on the circulation of people, ideas and goods.

UNRRA’s seed program is an excellent example. It offers a multi-faceted lens through which to ask questions about the expectations and limits of agricultural transformation, as well as the shifting power relations between farmer and supplier of agricultural technology. Studying the history of agencies such as UNRRA helps us understand the power dynamics between institutions, experts, crops, and farmers at specific times and in specific places. Ultimately it also raises larger questions, that are still at the heart of development today, namely of how technological innovation, be it in the forms of minuscule seeds or of massive infrastructure projects, is received and used, accepted or challenged by farmers.

If today we tend to associate rural development with so-called ‘peasants’ in the ‘Global South’, history reminds us that not so long ago Europe and its rural populations were a major site of development. From the 1920s onwards, state-sanctioned land reclamation, internal colonisation and land reform schemes existed in liberal democracies and fascist regimes ranging from the north to the south of the European continent. The concern with the future of farmers in Europe still dominated international fora in the mid-1940s, when rehabilitating European agricultural production was seen as a fundamental condition for peace. From the 1950s, traditional small-scale farming that relied on manual labour decreased as the sector became smaller, more industrialised and dominated by state and institutional interventions and the logic and regulations of the Common European Agricultural Policy. Therewhile, dominated by the Malthusian logic of feeding a growing population with limited resources, the attention of international organisations firmly shifted to Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

If today we tend to associate rural development with so-called ‘peasants’ in the ‘Global South’, history reminds us that not so long ago Europe and its rural populations were a major site of development.

In the second half of the twentieth century, agricultural development became strongly entangled with the rise of Cold War antagonism, its particular geopolitical contexts and agendas but also the cultural and scientific visions of the period. Asian, Latin American and to a lesser extent African ‘peasants’ became the targets of multilateral and bilateral development and aid programmes. The emergence of the so-called ‘Third World’ shaped the minds of development practitioners and experts and although the term has now gone out of fashion, the mental association of ‘backward’ rural communities, archaic working and living conditions, insufficient health care, illiteracy and malnutrition persists.

As the figure of the impoverished rural smallholder moved from a provincialised European countryside to more exotic tropical and sub-tropical settings, many of the development tropes, imaginaries, and remedies remained the same. In other words, the wheel of development that we associate with sustainable development goals today has been repaired from time to time but has never been taken apart completely.

By looking at the seed programme launched by UNRRA for newly-liberated countries in Europe between 1943 and 1947, we can reflect on the shifts and continuities between successive development and modernising strategies that took place in the wake of the Second World War. Using UNRRA records as a lens we can see the economic rationale of the seed programme, and the obstacles it encountered in specific countries. It shows how UNRRA official thought of seeds as immediate relief aid but also as so-called capital supplies with long-term economic ramifications. The story can in fact be told from many different angles: it is a story of agrarian transformation in the name of food security, a story of humanitarian aid and wartime relief, a story of the beginning of technical assistance and its geopolitical enmeshment. It is also a story about globalization, the rise of international organisations, expertise, science and technology.

Last but not least, it is a story of how local protagonists, agencies and farmers in the receiving countries accepted, and sometimes exploited the arrival of seeds through black-marketeering and, in certain places, rebelled against the imposition of new varieties by feeding them to their cattle or setting their fields on fire. History gives us the tools to explore complex narratives of global and local processes, environmental determinism and human agency. Through the history of UNRRA’s seed distribution in the late 1940s, we see a tension that still qualifies development today: tensions between the political, ideological and economic imperatives of development, and the social universe of the farmers who sometimes share transformative ambitions and sometimes defiantly guard their autonomy. To borrow Fullilove’s phrase for our own purposes, history, like seeds, is ‘an embodiment of things past’ as much as it is a ‘powerful signifier’ of future potential.