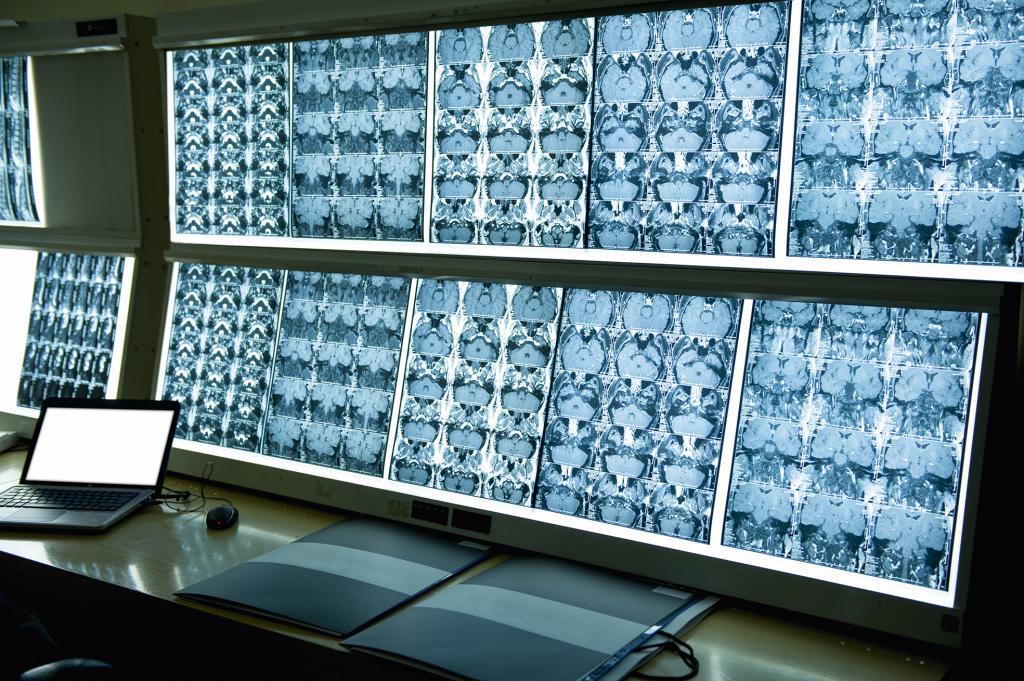

This technology has been a boon to diagnosticians, saving countless lives; however, despite the early and consequential invention of the CT scan, the health sector has been slow to embrace digitalisation.

Telemedicine never took off despite advances in internet connectivity and mobile telephony. Electronic medical records (EMRs), alternately called electronic health records to reflect a broader view of patient well-being beyond clinical data, were supposed to be another game changer.

By replacing thick dossiers of handwritten clipboard notes, EMRs are meant to enhance the portability and efficacious use of vital personal health information. However, they remain plagued by differing standards and suboptimal use: patients still carry piles of paper around or doctors fax their clinical records.

Wearables such as Fitbit, Garmin, Apple Watch and the Oura ring seem to be riding a wave of popularity. However, these fashionable wears for the affluent few are of little use when it comes to serious health conditions or affordable health care for the masses.

Half the world still does not have access to essential health services, and there is a global shortage of 18 million health workers – no wearable can substitute for them.

Radically innovative approaches are needed for quality and affordable healthcare; the potential is there despite the hype. Already, doctors in China and India routinely use WhatsApp or WeChat to receive diagnostic images and to respond rapidly to patient queries.

Hospitals such as the Samutprakarn Provincial Hospital in Thailand, which I visited recently, have eliminated paperwork in admissions and payments, reduced fraud and streamlined workflow with digital technologies.

In Israel the Clalit Research Institute has run predictive analytics on its health database to forecast renal failure due to diabetes years in advance.

The potential of large datasets coming together in real time to help identify public-health threats, such as the ongoing novel coronavirus epidemic, is also becoming apparent.

To realise this potential, new collaborations are needed to federate data, computing capacity, algorithmic expertise and governance approaches globally.

Such orchestration would require building a neutral and trusted platform that allows different constituencies – governments, international organisations, foundations, academia, private sector and civil society – to come together in a hub-and-spoke architecture dedicated to digital health.

It would also require a series of collaborative analytical and research projects, “pathfinder projects”, to build up a set of questions to be answered, research and implementation problems to be solved and repositories of possible ways to cooperate and build capacity.

This article was published in the latest edition of Globe, the Graduate Institute Review.