One of your latest papers, “Tax Administration and Compliance: Evidence from Medieval Paris”, is devoted to the Parisian taille of the late 13th century, which was a kind of taxation mechanism used by the French Crown to finance big periodic expenses. How did you become interested in the taille?

of International Economics and new director

of the Centre for Finance and Development.

I was working on data from the tax roles in a study of inequality in Paris. A number of studies utilised tax rolls to infer about medieval and early modern income inequality. What caught my eye was that the tax quotas were always collected and that the rich contributed most of them. It then struck me that the city leaders of Paris found a way to achieve tax compliance that did not cause civil unrest. I found this to be a big contrast with current tax evasion practiced mainly by the wealthy. The mechanism used by the city leaders arose in a period when Paris grew much faster than other cities in Western Europe. Neoliberal advocates argue that taxes cripple economic growth and that when you tax the rich they either move their fortunes to tax shelters or relocate to them. Paris’s experience shows that this is not necessarily true and that a community can adopt a set of norms that overcome these negative side effects of taxation. The Paris taille is inspiring, especially for lesser developed economies where the central government cannot effectively tax, as it demonstrates that communities can work together to raise revenues for civic projects and that the rich, while paying more taxes, benefit from city growth and low violence and crime.

Were there similar taxation mechanisms in other European regions?

This tax mechanism was not unique to Paris. It existed elsewhere (and was also adopted after the success in Paris), mainly in smaller communities. But the case of Paris is unique because the taille was applied to a metropolis rather than an intimate community. However, the norm, at the time (and in Paris subsequently), was to employ tax farmers rather than a communal mechanism to raise taxes for the government. Tax farmers generally shifted the tax burden from the elites (who were able to evade them) to the middle classes and the poor.

Among all your research interests, which of them do you consider to be your specialised “research” identity?

My research topics are varied and stretch across time and subfields of economics. My main field of research is financial history and development. My research identity is formed not only by my field of research but also by my reliance on novel, archival data that I extract myself (as opposed to using available data). These new data allow me to formulate new research hypotheses or challenge existing ones – and so to contribute to the literature in economic history.

What is your current research project?

My current research project is on the development of capital markets in England in the 17th century. I chose this topic of research because, when teaching this period, it always intrigued me that the reign of the Stuart monarchs was seen as a “the dark ages” in English (economic) history, ending with the Glorious Revolution of 1688. I always thought this framing of the Stuart regime was done by those that deposed it and therefore might not be historically accurate. In particular, I always wondered how London could be rebuilt so quickly after the Great Fire of 1666 if capital markets did not exist and property rights were not protected.

Could you briefly describe your philosophy of teaching?

I believe that students today have access to knowledge and facts and my role is to provide them with tools that allow them to critically acquire this knowledge. My role as a teacher is similar to that of a coach; I select the topics that I think are important for them and encourage them to do the hard work necessary to master them. I also greatly appreciate class discussion and peer learning. I believe that only through active preparation and participation can real, deep and meaningful learning take place. My aim is that what students learn in my classes will not be forgotten after the final exam and will be useful in their future.

What courses will you teach and how have they been informed by your research interests?

I am planning to teach, in the Spring semester, a course in economic history and a course in financial development. While I include pieces from my own research in both courses, my aim is to provide students with the motivation not to replicate my work, but to pursue their own ideas (I never assign topics for theses). I select material that motivates me to do research and, of course, use my own research to exemplify its application.

What have you read lately that has marked your academic discipline?

A book that I must recommend is Ran Abramitzky’s The Mystery of the Kibbutz. It is a fascinating read on how a voluntary collective enclave survived for so many years in Israel. While the book is a scientific research, it is so well written that it engages the reader. It won the best book prize in economic history awarded by the US Economic History Association.

Which academic articles or books would you like everybody to read?

Among articles that are a must-read in economic history is Avner Greif’s “The Fundamental Problem of Exchange”. Greif was inspired by documents from the Cairo geniza – a repository of a medieval Jewish community – to formulate an important idea: all exchange is sequential and there is a potential commitment problem to complete transactions as planned (promised). He argues that historically people solved commitment problems by using informal reputation mechanisms. The article is truly inspiring as it shows how far-reaching insights in economics can be inferred from historical documents. Another paper that I really like to teach is “Legal Origins” by Edward Glaeser and Andrei Shleifer. It shows how a relatively simple economic framework can be used to explain the divergent development of England’s and France’s legal systems from the Middle Ages to today and how the financial system of countries adhering to the Anglo-Saxon system developed differently from that of countries adhering to the Continental one. Finally, I must recommend “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution” by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson. In this paper the authors set the stage for an extremely fertile line of research that uses exogenous events or variables to identify the role of institutions in explaining the economic growth and development, and the economic divergence between “North” and “South”.

Do you have any special memory from your PhD years that you would like to share?

When I was a graduate student at Berkeley and about to complete my dissertation, I was worried about job market outcomes and whether my papers would be published and where. My advisor, Barry Eichengreen, gave me an advice that I pass on to my students; he simply told me, “Nathan, concentrate on the fundamentals.”

If you were to help a prospective doctoral student to formulate his research question, what would your advice be?

As I explained earlier, I don’t see my role as an advisor by telling students what they should research. I encourage them to work on what interests them. By selecting issues that they are interested in, one can be sure that the motivation to complete the doctoral journey is there. Of course, I also see my role as helping tailor the research proposal to interact with existing knowledge and pinpointing its expected contribution, right from the start.

* * *

- Read here Professor Sussman’ paper “Tax Administration and Compliance: Evidence from Medieval Paris”.

- Find out more on his current research project on the financial development of London in the 17th century here.

- Read also an interview in which Professor Sussman speaks about his motivation for joining the Institute and his appointment as Director of the Centre for Finance and Development.

Interview by Bugra Güngör, PhD candidate in International Relations and Political Science; editing by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.

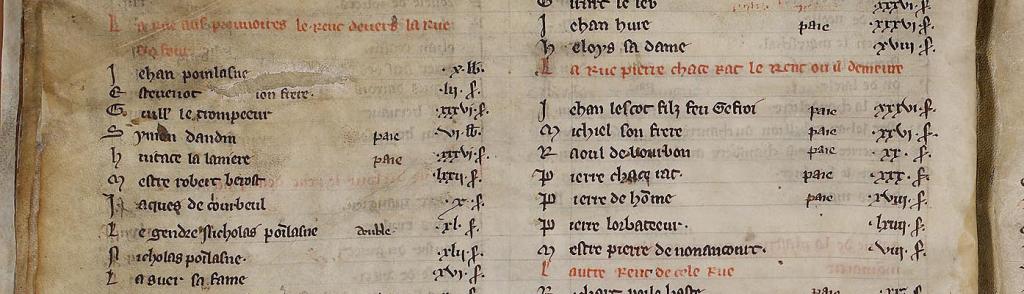

Banner image: excerpt from Rôle de la taille à Paris (Archives nationales [Public domain]).