How did you come to choose your research topic?

As if often can happen, by a fortunate accident! I was initially ethnographically pursuing how new regional identities were being crafted in the India-Myanmar border areas, particularly with the emergence of a new phenomenon of “battlefield tourism” that drew upon global imageries of WWII. I realised that there had been no rigorous academic work on the subject of the war apart from numerous memoirs. It also increasingly led me to realise that the war has more lasting and pertinent effects on the way the entire borderlands were shaped, which had not been recognised adequately.

What were your main research questions and your methodological approach?

The thesis was motivated by the following questions:

- How did WWII shape the emergence of nation-state borderlands in what were formerly loosely defined frontiers of empires?

- How did cultural and military knowledge come together in this process?

- Can we recognise the globalising force of WWII (for example, the coming of new technologies of mobility) as a preface to the postcolonial histories of securitisation and development, including the rupture between South Asia and Southeast-Asia?

Moving away from Partition-centric histories of South Asia, my thesis seeks to bridge academic and actual spatial divides that separated these nation-states – by bringing together South/Southeast Asian histories together, and by actually looking at sources and phenomena from different sides of the border. In fact, the division into South/Southeast Asia occurred after WWII. I use the conceptual lenses of wartime “loyalty” and “morale” to structure the narrative and give coherence to what were otherwise very fragmentary and scattered themes. The chapters each deal with information, objects (guns), bodies (and mutilated remains like head-hunting trophies), landscape and technology respectively.

What findings did you make?

I found that this region become “marginal” despite a “globalising” event like WWII, when new networks and technologies of connectivity arrived in an unprecedented manner. It turns out that selective policies of state-making and emerging challenges they faced from rivals resulted in making this region a “remote” place. Allied armed forces and the post-war British government had left the process of demobilisation incomplete in a time of impending decolonisation. This created fertile conditions for new armed conflicts to emerge.

The narrative of isolation and marginality in general has since dictated both the politics of conflict and the politics of development on both sides of the India-Myanmar borders. Simultaneously, this notion that the region was an “ungovernable” space after the war has been long used to favour arguments for greater securitisation of borders and use of oppressive legal regimes.

Can your historical approach help understand the ongoing conflicts in the region?

The insights from the thesis speak to the present-day rhetoric of “national security” being threatened from within in both these nation-states, whether this rhetoric is about the expulsion of the Rohingya or the increased militarisation in border areas such as Kashmir or talk of enhancing connectivity and development in Northeast India. If we step back and take a historical view, we can see how these places have come to be portrayed as dangerous places that threaten national harmony – which is still used to justify the use of extrajudicial coercion. It is also significant that much of the military infrastructure in place today in Northeast India is directed towards threats from China, but is also used in internal counterinsurgency operations, both of which came directly from the war. So, selective military infrastructures have been instituted historically while the rest of the region has been left underdeveloped. During the war, the British state was vulnerable as it particularly struggled to perform its sovereignty, and had to look for alternative ways to showcase it when faced with external and internal competition. Such selective and uneven alternatives to liberal concepts of state-making continue to be dominant in the borderland region.

Similarly, there is a long-standing continuity between colonial practices of counterinsurgency and coercion against civilian populations, or strategies of “winning hearts and minds” by the provision of developmental goods, and both go hand in hand. The thesis also exposes the hypocrisy and racial nature of the still-prevalent narrative of a “good war” as atrocities and excesses were committed by all sides, which the Allied nations tend to underplay, putting the blame on the Japanese. More significantly, the binary notion that the various local ethno-racial minorities across these borderlands had either been “loyal” collaborators either with the Allies or the Japanese had important implications in shaping the discourses of self-determination, citizenship and the legitimacy of armed conflicts that emerged soon after.

How can your research findings serve society?

In my thesis I show how many ethnic categories had been made and un-made due to warfare. Similarly, cultural knowledge in the form of racial and ethnic stereotypes was also used by colonial administrators quite flexibly and inconsistently to justify immediate needs – let’s say arming one ethnic “tribal” group over another. All this reminds us that social categories are not given facts; they have been produced by human beings and can change over time. This notion can be generally useful, especially in contexts where discourses of difference between social categories and cultural arguments are used to further discrimination, hate and exclusion. Such politics have privileged the making of boundaries of cultural difference over inclusion.

So, given your findings, what should be the focus of politics?

One purpose of cultural knowledge and arguments based on cultural stereotypes has been to represent people and places as “dangerous” in military-policy circles, and thus deserving of extreme measures including violence (the War on Terror and today’s drone warfare are classic examples of this). Within the regional context, this can be observed for instance in the way the rhetoric of preserving “tribal culture” and territory has been used for channelling selective development. At a time when ceasefire agreements are being negotiated with various armed insurgent groups, and new development policies are being envisaged, it would behove policy thinkers to be more aware of the selective and ambiguous nature of governance here. Arms proliferation, illicit trades and lopsided development have become part of a political economy where liberal state-making has not been able to extend its foothold since the end of WWII. Performative, short-sighted and ad-hoc measures that only tend to perpetuate this situation can hardly be expected to lead to lasting solutions for peace and prosperity in the region.

What do you plan to do now?

I would ideally like to pursue a postdoc project that investigates the question of how the region became more “remote” after the war, by focussing on some of the insurgencies that emerged across the two borders and on policies of selective development that have allowed these phenomena to thrive. The period covered will roughly be from the end of WWII till the early 1960s’ Chinese military invasion into northeast India.

* * *

Aditya Kiran Kakati defended his PhD thesis in International History in May 2019. Professor Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou presided the committee, which included Professor Gopalan Balachandran and Professor Shalini Randeria, thesis co-directors, and Professor H.W. (Willem) van Schendel, from the University of Amsterdam.

Full citation of the PhD thesis:

Kakati, Aditya Kiran. “Living on the Edge: How Encounters with Global War (WWII) Re-Made the lndo-Burma Frontiers into Bordered-Worlds.” PhD thesis, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2019.

* * *

Interview by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.

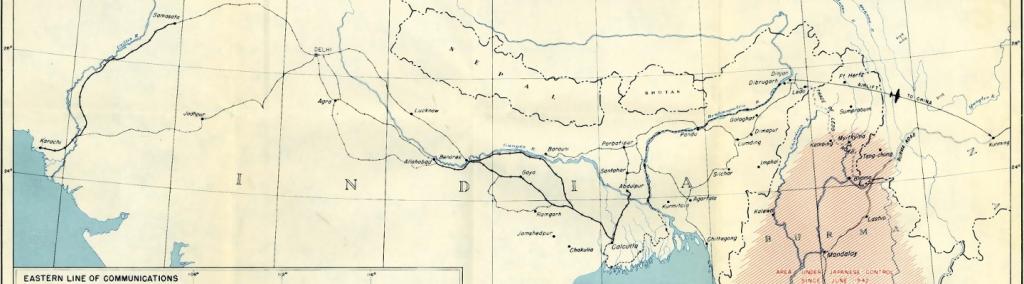

Banner image: excerpt from a map depicting the transportation routes in the China-Burma-India theatre, 1942–1943. United States Army. (Public domain.)