Grégoire Mallard’s book makes three major interventions. The first one looks at the classical anthropological concept of the “gift” (or in French, the système de prestations réciproques) developed by Marcel Mauss in his famous essay, a concept that has since been widely written about and used to study empirical realities, including in contemporary domains such as corporate social responsibility. The book starts by examining the political and historical context in which Mauss evolved in order to understand what kind of problems he was trying to address. This required historical archival work into Mauss’s various networks, involving learned societies such as institutes of ethnology, his links with other anthropologists like Malinowski and his political activism, especially his role in the founding of the French Socialist Party. Archives were indispensable for discerning the discursive context in which the concept of “gift exchange” was circulating at the time – and they showed that this seemingly novel concept was not at all new.

In fact, the concept was already quite embedded in the language both of French colonial law and international law. It is visible in contractual agreements with colonised peoples and can also be traced in the reformist thinking that livened debates about colonial relations: it is through the idea of prestations réciproques that reformers of colonial law, including Mauss, referred to the future relations they wanted to see created between Metropole and Colony, especially in debates about issues such as forced labour. Anthropologists used the concept to talk about non-monetised exchange value systems. Recognising its colonial origins has great implications for understanding how the concept was later used and interpreted in international legal agreements between European nations after the First World War. For instance, the Treaty of Versailles and the issue of reparations that Germany had to pay after losing the war were also couched in the language of prestations réciproques. Thus the concept travelled from international politics to anthropology and back to politics, and Professor Mallard’s book shows how Mauss took an active part in this process through his involvement in important colonial debates about the “Congo Question” in the early 20th century, and his later conversations about reparations.

The second key intervention of the book is to show the presence of Maussian concepts in the efforts, till the 1980s, to decolonise international economic governance in the aftermath of the wave of political independences in the 1960s–70s. Professor Mallard approaches the history of the New International Economic Order (NIEO) through anthropologists, legal scholars and political statesmen who lobbied for the NIEO in 1970s. He links their position to the pre-independence context of French Algeria. Indeed, the shifting use of Mauss’s concepts in the 1920–30s went on beyond his lifetime into the 1940s–50s post-WWII contexts, leading up the 1970s. A most evident example is the fact that several colonial administrators or policymakers, like Jacques Soustelle, who were involved in shaping French Algerian policy, had been Mauss’s PhD students and used his concepts of gift exchange and prestations réciproques to re-think the new bonds between France and Algeria in the time leading up to the latter’s independence, precisely to avoid the dissolution of the politico-economic links between the Metropole and Algeria. This was the discursive background against which NIEO thinkers, like Mohammed Bedjaoui, wrote about the necessity to denounce fake gifts and propose a renewed global contract. Many anthropologists and legal scholars ignore this legacy as, after the Algerian war, ethnologists, like Pierre Bourdieu, had to obscure how these ideas had been utilised in the Algerian context for political purposes.

The third intervention that Professor Mallard makes in his book responds to more contemporary concerns in the sociology of finance and is motivated by his interest in the Greek sovereign debt crisis and more largely in European sovereign debt politics. In a last part, he explores how eurozone members have thought about the question of “solidarity”, which emerges from European treaties as well as from political speeches of French economists on the need to reform the current euro-governance and enhance solidarity mechanisms, for instance through debt cancellation/mutualisation or spreading the horizon of debt reimbursements to infinity. That’s when one of the book’s major contributions unfolds, as the author brings back the history of “gift exchange” to interpret some of the proposed remedy policies to the current European debt crisis. It becomes clear that the concept pervaded the intellectual framework of French economists, including the French heterodox school, who participated in the creation of the euro under the socialist leadership at the time of the Maastricht Treaty. In the context of the post-Maastricht Treaty negotiations, very far from that of the 1920s, they were reading, citing and using Mauss extensively, and “gift exchange” was the subject of many of their publications. The Greek debt crisis was to expose the distance between reality and this planned eurozone.

Overall, the book shows how these reinterpretations of a concept are important to consider within the history of capitalism and its continuous re-invention, which has been marked by “crises” and “failures”. In many ways, these crises are not just economic in kind, and felt by massive destruction of wealth, but they are also epistemological, in the sense that they question the validity of the heuristic models that experts, economists and legal scholars draw upon when thinking about economic governance and the nature of economic exchanges. Sociologists of knowledge can thus help financial historians understand the sociocultural genealogies of key theoretical concepts and the types of disciplinary knowledge practices that are associated with their use in different contexts. By bringing these genealogies to the fore, the book tries to show how historically, various disciplines tried to define the nature of good economic governance along a North-South axis, both at the global and inter-European levels, and in doing so, how they have deployed the concept of gift exchange to frame international economic governance before and after decolonisation.

* * *

Full citation of the book:

Mallard, Grégoire. Gift Exchange: The Transnational History of a Political Idea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Freely available on Cambridge Core: doi:10.1017/9781108570497.

* * *

By Aditya Kiran Kakati, PhD candidate in International History and Anthropology and Sociology; edited by Nathalie Tanner, Research Office.

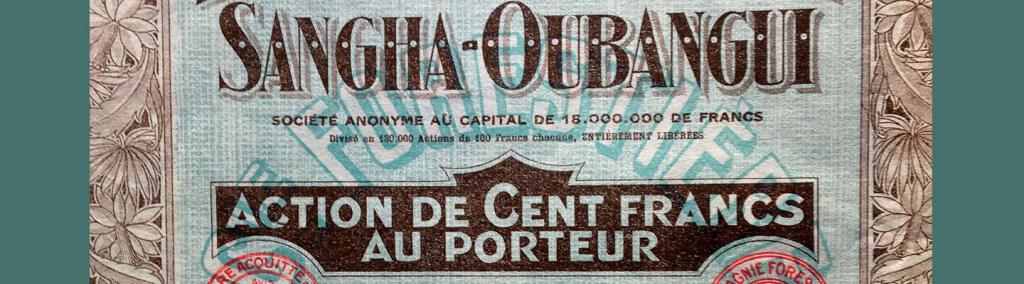

Banner image: extract from the cover picture of Grégoire Mallard’s book, showing the photo of a stock of the Compagnie forestière Sangha-Oubangui. Author’s private collection.