The pandemic caused by the spread of covid-19 and the economic consequences of the measures taken to mitigate it are putting Latin American political systems in tension. Our series of webinars explore the effects of the crisis on democracy and state-citizen relationships across countries.

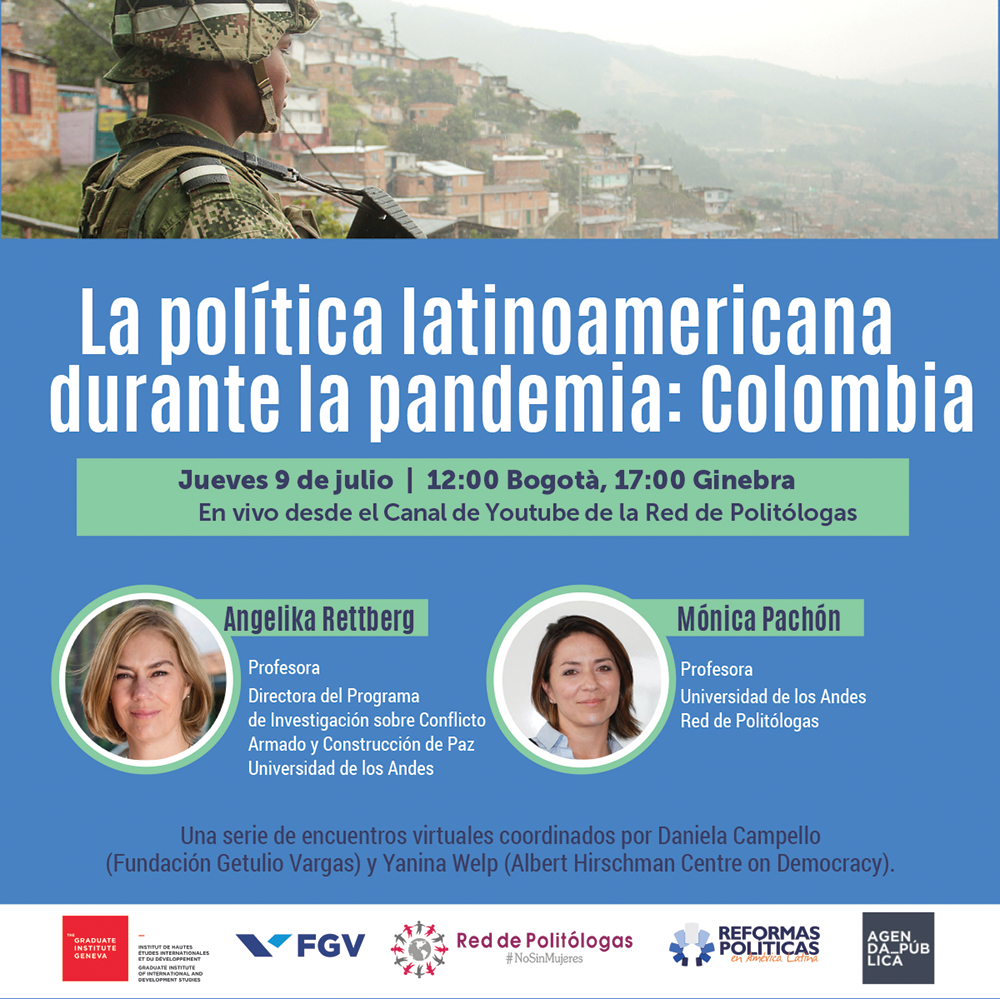

The case of Colombia was on focus on July 9, 2020, with the participation of Angelika Rettberg (University of Los Andes, Red de Politólogas) and Mónica Pachón (University of Los Andes, Red de Politólogas).

The events are coordinated by Daniela Campello (Getulio Vargas Foundation) and Yanina Welp (Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy).

The situation in short

In 2016, after a failed plebiscite the parliament ratified the peace agreements, leading to the demobilization of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - People's Army (Spanish: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - Ejército del Pueblo, FARC – EP) and its transformation into a political party. As part of the Accords, it was agreed to implement policies to promote the economical development in the areas previously affected by the guerrilla. In 2018, Ivan Duque (Democratic Center) assumed the presidency. Duque represents a hard line, heir to that of former president Alvaro Uribe, who campaigned against the peace agreements in the 2016 plebiscite. In October 2019 there was a strong social outbreak in which various claims anchored in social and environmental policies converged. Colombia faces the pandemic within this scenario of erratic application of the peace accords and social conflict, to which is added the pressure exerted by the Venezuelan migratory crisis (the Venezuelan population that would have displaced to Colombia is estimated at more than two million). This results in a dramatic change of agenda and a dispute over scarce resources, where xenophobic feelings grow and organized crime proliferates. Guided by expert committees and the advice of the WHO, the government has implemented a harsh quarantine and has invested in improving the health system; but despite that, contagion continues their upward evolution. Although the government makes decisions unilaterally, the different territorial units also intervene without higher levels of conflict. This situation of the leadership and the political parties (characterized by weakness) added to the high electoral abstention in the country suggest that the crisis of democracy will deepen shaping more disengagement.

Main points emerging from the conversation

1. A tragic change of agenda dominated by uncertainty

With the Peace Accords and the Venezuelan migration crisis as a backdrop, in 2019 Colombia was one of the countries in which there were social outbreaks. According to the experts in our conversation, the heterogeneous demands raised at that time reflected a debate with an eye toward the future. The Peace Accords and other social and environmental policies were at the center of the agenda, but now they have been displaced by the need to provide immediate responses to pressing economic and health needs.

2. An unprecedented economic crisis

There has been a rapid and surprising growth in poverty. Mónica Pachón emphasizes that the management of the pandemia will lead to a better evaluation of the public health system, since investment has increased, but in all other areas the indicators are negative, inequality, poverty and unemployment will grow. The speed with which the crisis has erupted would also show that the economic strength was less than the perceived.

3. Unilateral decision making and political weakness

On March 22, a strict quarantine was decreed in the country. On April 27 some economic sectors were opened but for the general population, the quarantine has been extended (after the conversation was held, it has been extended again, for the eighth time, until August 30). Our analysts emphasize that policies are decided based on scientific evidence, yet leadership is weak. Parties hardly exist at the subnational level (with many movements created for each electoral contest). The capital, Bogotá, is the most affected city. The mayor Claudia López (the first woman in the position as well the first openly homosexual person) is in the hands of a party opposed to the national government, but there have been no strong tensions between national and local governments. The legislative assembly has had little activity. Decisions are made by decree and are implemented at the municipal level. There are acceptable levels of coordination.

4. The ‘flourishing’ of organized crime

Angelika Rettberg points out that in the cities the confinement is endless but lax, without greater police or military presence. However, in the peripheries, the networks of organized crime have taken charge of supervising compliance with the quarantine because this situation facilitates their illicit businesses, which have proliferated in these circumstances.

5. Growing xenophobia

Colombia's action regarding Venezuelan migrants had so far been notable for its human orientation. In the context of the pandemic, with the growth of crime and the greater dispute over scarce resources, there is a backward movement and critical situations of xenophobia arise. A few migrants returned to Venezuela when they were left without income due to the confinement, but millions are in Colombia, many of them in extremely vulnerable situations.

6. No International aid for an extreme situation

If in previous emergency situations, international organizations such as the Inter-American Development Bank or the UN had always emerged as relevant actors, this time they are conspicuous by their absence. There is no companion action, no help, or leadership to accompany the solution or mitigation of this crisis, says Angelika Rettberg.

Link to the full event in Spanish: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6Ypz8WgsPo